Continuing the conversation with Charlayn von Solms…

SM: Your first main work using the poetics of Homer, A Catalogue of Shapes, was the subject of a dissertation for your PhD at UCT, supervised by a Classicist (Prof. Clive Chandler) and a Fine Artist (Prof. Bruce Arnott). Was the PhD part of an attempt to have a fine-tuned and also academic understanding of the dynamics of Homeric poetry?

CvS: As I was appropriating aspects of a theoretical field in which I’m not a specialist, I really had to be respectful of its complexities. The PhD format meant that I could not freewheel it. There would have to be a significant degree of rigour in terms of how I dealt with the Homeric material.

SM: A Catalogue of Shapes is a carefully designed set of individual ‘character’ sculptures that combine in a complex arrangement in the museum space. Can you explain the design of the whole?

CvS: A Catalogue of Shapes was intended to function as a type of portrait known as a ‘composite object portrait’ which is a representation based not on physical likeness, but expression of a subject’s core characteristics by means of multiple visual elements. As the portrait here is of Homer as a compositional system, the aim was to provide the viewer with the opportunity to be in the position of the performer: to navigate a set of characters, relationships between those characters, plot-lines and various recurring compositional elements. Of the twelve characters represented, some are obvious choices, but others less so. Prominent characters like Zeus, Hera, Paris, etc. are all absent, but Ate and Eris are there. The aim was not to create a major players’ cast list, but to establish sets of interactive pairs derived from a primary pair – Odysseus and Achilles – as the two characters whose actions define the epics. One of my favourite Homeric strategies is the definition of one thing in terms of another. So, the sculptures were designed as similar and antithetical pairs, with each character forming part of more than one set.

SM: You speak about sculptural assemblage as your technique. How do you select the components to assemble an individual piece?

CvS: I use assemblage as a form of material metaphor. So, the first thing I do is to get a running list of a subject’s various character traits, activities, and other attributes on a loop in the back of my head. At this stage, to make the list as extensive as possible I’ll spend a lot of time with my dictionary and thesaurus. I then try to think either of what type of functional mechanism that subject would be, or more simply, what type of object shares one or more of those attributes. The first object selected for A Catalogue of Shapes was an old orange fishing buoy. I’d been walking around for days thinking about Odysseus when I went to the flea market and recognised the heavily tanned, ocean-beaten and weather-worn Homeric hero in it.

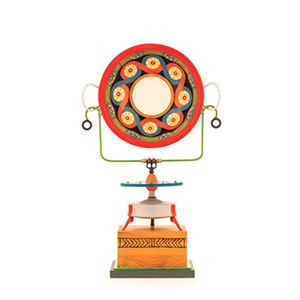

Odysseus, 2010 (photo credit: I.C. Grobler)

Odysseus, 2010 (photo credit: I.C. Grobler)

SM: That seems so random, yet it is just perfect for Odysseus.

CvS: Being open to happy accidents is an inescapable part of making assemblage. But there is also a very deliberate aspect: as each successive sculpture in a series is partly a response to those that precede it, objects such as the buoy can become important recurring rhythmic elements. At other times, I’ll know exactly what type of object I’d like to use – such as the colander in Kalypso – so then it is a matter of finding an example that most closely matches the example in my head. Apart from these objects, there are also those that perform a formal or compositional role where the shape or structure of the thing is more important to me than its function. It is also not unusual to use sections of objects. The best moment is when I find an object that has the right shape, but also works conceptually in terms of what it is – such as the snaffle bit in Nestor.

SM: I love Penelope’s embroidery hoop for that reason too. Do you ever make components, or are they always ‘found’?

CvS: Most of my works contain at least one self-made element. Where the appropriated element is not a specific object, but a particular type of shape – such as the concertina in Odysseus – I will craft it myself. The composition of the sculpture occurs on paper first. It will begin as a series of rough sketches, I’ll go and find at least some of the objects I plan on using, and then move on to making a drawing to the same scale as the planned sculpture. I do it this way because geometry is very important to me. The proportionality of elements and how they relate to one another are carefully worked out through a process of drawing and redrawing until I’m happy with what I see. The drawing stage is also where I begin to incorporate elements such as colour, pattern and motifs that are not present on the objects but are as much appropriated elements as the objects are. Only then is the sculpture itself made. While the drawing provides a template, I will often veer from its design where a better solution presents itself during construction.

SM: How does Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25 lead on from A Catalogue of Shapes?

CvS: The aim of Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25 was to explore the allusive potential of Homeric catalogues. Narrative here is less dependent on a clearly identifiable plot than the establishment of patterns. The structure of this series partly retains the pairs-based convention established in A Catalogue of Shapes. Four of the sculptures – Ares, Herakles, Nestor, and Asclepius – function as members of both similar and antithetical pairs, a format similar to A Catalogue of Shapes. Another set cuts across the space created between the first four. This set also has four members but no pairs. Here it is Thamyris against three Muses named for the attributes they took from him – voice, memory, and technique. A ninth sculpture representing Apollo sits behind Thamyris, but beyond the boundary created by both groups. As Achilles’ divine nemesis, this god features prominently in the Trojan catalogue but not in the Catalogue of Ships. However, the reference to Eurytos in the story of Thamyris draws a parallel between Apollo and the Muses as benefactors turned punishers (in a rare Iliadic allusion to the Odyssey, Odysseus speaks of Eurytos’ fate in Book 8 alongside a mention of Herakles as a fellow archer). Apollo as healer and killer also connects to the set comprising Ares, Herakles, Nestor, and Asclepius by combining its antithetical attributes. Yet again, the choice of characters is not a direct reflection of those that feature in the text, but an exploration of what may be an implied narrative within a catalogue.

SM: Which is your favourite piece?

CvS: Whichever one I am working on at the time.

SM: What are you currently working on?

CvS: I’m feeling stupidly brave. So, I’m attempting to make sense of those muses again.

To contact Charlyn e-mail: charlayn.vonsolms@alumni.uct.ac.za

Book info: A Homeric Catalogue of Shapes: The Iliad and Odyssey Seen Differently. Bloomsbury, 2020. Part of a the Imagines series on classical receptions in the visual and performing arts (series editors: Filippo Carlà-Uhink and Martin Lindner). Available at https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/a-homeric-catalogue-of-shapes-9781350039582/

Website: https://charlaynvonsolms.com/

To contact the African Takeover email: masters@sun.ac.za