This post was written by Egas Bender de Moniz Bandeira who is a research fellow at the Department of Classics and Asian Cultures of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, and an affiliate researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory in Frankfurt.

Ancient Greece plays a special role in modern Chinese imagination and discourse. Understanding it as the cradle of Western civilization, many Chinese intellectuals strive to study ancient Greece in order to better understand the “West” as a whole. This interest for ancient Greece at times became so strong that Mao Zedong (1893-1976), in 1941, famously complained that some of his compatriots were more familiar with Greece than with their own country.

It is interesting to note that Mao, in the original, just spoke of “Greece,” while the official English translation adds the specification of “ancient.” The term he used, Xila 希臘, is a phonetic rendering of Hellas, used to denote both ancient and modern Greece. Although by Mao’s time it had long been universal across all Sinitic languages, it was historically not the only Chinese name for “Greece.”

In this post, rather than retracing any specific instance of classical reception in modern China, I would like to take a look at the very names for Greece in Chinese, and explore what they tell us about translations and perceptions of European history. In particular, I would like to make two points. First, the decision to use a rendering of Hellas rather than a Chinese name for Greece was very likely the decision of a German Protestant missionary, whose originalist approach diverged from previous naming conventions. Yet, it was used in a number of influential publications, and it proved to be overwhelmingly successful, given the important role of Greece in the Chinese discourse of the time, which stressed the significance of ancient Greece and the creation of the modern Greek nation-state.

However, and this is my second point, the narrative of unity between ancient and modern Greece did not go entirely uncontested. To this end, I uncover a forgotten episode of the 1880s, when a leading Chinese newspaper started to use a different name altogether, arguing that modern Greece ought to be differentiated from ancient Greece. Somewhat ironically, although the name it proposed for modern Greece – Wuchi 烏遲 – is relatively obscure, it likely goes back to antiquity itself, stemming from an ancient Chinese rendering of the city of Alexandria in Egypt.

“Greece” had been known in Chinese since the 16th century by various renderings of the ultimately Latin name Graecia: Elejiya 厄勒祭亞 (also written 額勒濟亞), Eleqiya 額勒齊亞, and others. These forms were mediated through the modern Romance languages spoken by the Jesuit missionaries who introduced knowledge about Greek and Roman antiquity as well as about current European geography. Together with the name, it should be noted, these missionaries also brought with them the narrative of ancient Greece as the origin of European civilization. For example, Giulio Aleni’s (1582-1649) Records of the lands beyond the imperial administration (Zhifang waiji 職方外紀), published in 1623, describe Elejiya 厄勒祭亞 (2:17a-b): “Her fame is known across the world, and her rites and music, laws, alphabet, and classics are all the ancestors of Western lands.” At the same time, the records also note that “now she has been thrown in disorder by the Muslims, and is no longer what she used to be.” From that time, as research pioneered by Xin Fan and Barbara-Almut Renger has shown, elements from Greek antiquity came to play a special role in the East Asian imagination and to be used for a wide range of discursive purposes—and in many ways continue to do so today.

By the turn of the 19th century, other names had appeared. Sources like Lin Zexu’s (1785-1850) Record of the four continents (Sizhou zhi 四洲志) speak of Elixi 額力西 (written as 額利西 or 額里西 elsewhere). This seems to be a transcription of the English term Greece, and thus to indicate the changed channels of global communication.[1] But yet another terminological innovation proved to be the most influential: Xila, for the first time a rendering of Hellas.

The way in which foreign words are rendered in Chinese languages often tells us about their trajectory. It is commonly thought that the rendering Xila is based on Cantonese, where it is pronounced Hei1-laap6 (or, in the contemporary colloquial Hong Kong variant, Hei1-lip6). Indeed, given the roles of Canton (Guangzhou) and later Hong Kong as key centres for trade, Cantonese was the gateway for a significant amount of translations into the Chinese languages.

However, I would like to suggest that the Cantonese etymology is not fully accurate. The pronunciation of the onset consonant in Cantonese (/h/) is closer to the English and German pronunciation of ‘Hellas’ than that of Modern Standard Mandarin Xila (/ɕ/). Yet the Cantonese pronunciation ends in a final consonant / p̚ / that cannot be easily explained as a careless permutation of the ending /s/ of ‘Hellas.’ What is more likely is that Xila reflects the pronunciation of the Mandarin koine based on the Lower Yangtze speech around the former capital Nanjing, which was highly prestigious at the time. There, the onset consonant had not yet palatalized to /ɕ/, but the final stop -p had been reduced to a glottal stop, corresponding to a pronunciation that was fairly close to the English or German one.

While the translation seems to be aimed at the Lower Yangtze Mandarin koine, this does not mean that it was coined in that region. Rather, the sources point us towards Singapore, which was then under British control. The term Xila is first attested in 1837/38 in the periodical Eastern Western Monthly Magazine (Dong xi yang kao meiyue tongji zhuan 東西洋考每月統記傳). This publication was edited between 1833 and 1839 first in Canton and, then from 1837, in Singapore by the German missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff (1803-1851), who later came to work as a British civil servant in Hong Kong.

The magazine published a series of articles on ancient civilizations as well as modern countries, including two on Greek history. Apart from locating Greece geographically, both of these were restricted to ancient Greece, introducing aspects of Greek mytho-history like the Trojan War. At the same time, as Wei Wei 韋巍has argued in a recent article about mid-19th century perceptions of ancient Greece, the articles gave a local flavour to these descriptions, such as calling ancient Greek gods “Bodhisattvas,” possibly showing the marks of editing by Gützlaff’s native assistants.

But why did Gützlaff choose to coin a new translation for Greece based on Hellas? Gützlaff did not explain his word choice, but we can surmise from the context. Gützlaff’s overall approach to translation was originalist, going back to Biblical source languages. In fact, Hellas was not his only innovation in which he preferred to use an ancient, original name instead of the more current modern one. Both the journal and Gützlaff’s translation of the Bible into Chinese call Egypt Maixi 麥西, based on the Hebrew designation Mizraim found in the Bible (which is, incidentally, also cognate with the modern Arabic self-designation, Miṣr).

Gützlaff’s (1803–1851) influential Complete Universal Geography (Wanguo dili quanji 萬國地理全集), published in 1844, picked up both names, as did another influential encyclopedia of the time, Xu Jiyu’s Concise Records of the World (Yinghuan zhilüe 瀛寰志略), published in 1849 (although it was not consistent in the case of Egypt). The definition of Greece in Xu’s encyclopedia was re-used in many further works of the 19th century, and reflects both past and present: “Xila (Elishi, Elixi, Eleji, Elexiya) is a famous country of antiquity that has now been re-created.”

In contrast to Maixi, Xila stuck as a translation for Greece in general usage. Based on the first few attestations in the late 1830s, one might say that the coinage of the Chinese word Xila based on “Hellas” was due to a German missionary’s decision. Its enduring success, however, probably had to do with the importance of Greece in the Chinese imagination of European history, as well as with the establishment of the modern Greek state and the renewed interest for Greece in the wake of romanticism. In this vein, Wei Wei argues that this return to the self-reference of Greeks consolidated various narratives about Greece, and “signified the transformation of the ancient Greek traditions revived in the Middle Ages into the narrative of Greek civilization underpinned by the idea of civilization.” Wei argues that the concept of Xila thus created in the mid-19th century was a co-production between Western and Chinese intellectuals, and emphasizes that:

“the relevant discourses to some extent overlook historical ruptures and accentuate the continuity and wholeness of the civilization. Xila often encompasses both ancient and modern times and can refer to the entirety as well as specific parts.”

It is surprising, however, that not everyone in 19th-century China agreed with the historical construction of modern Greece as a continuation of ancient Greece. Beginning from September 1881, the Shenbao, the leading Chinese-language daily newspaper published in Shanghai, started to use an entirely different name for Greece: Wuchi 烏遲. In total, the name appears in twelve articles, nine of which were published in April and May 1886, when hostilities between Greece and the Ottoman Empire led to a coastal blockade of Greece by Western European powers. After this dramatic news, mentions of the name Wuchi suddenly disappear.

The term Wuchi first appears rather randomly without any explanation at all, in an article about British subjects taken for ransom in various places. At least one of the articles that used the name seemed to be slightly confused about its origins. After reproducing news from the London Telegraph (which, in the original, spoke about “Greece”) about the incipient blockade and imminent resignation of Prime Minister Theodoros Diligiannis (1820–1905), the Shenbao added the following editorial comment: “What is called Wuchi in Western languages is actually what is called Hellas (Xila) in Chinese. It is a tiny small country, but wants to oppose all the Western countries. It is in danger indeed!” (Shenbao, 12 May 1886)

However, one of the other articles gives an extensive background of the situation, allegedly based on “extensive research of historical records and reading of Western books,” accompanied by a rationale for the use of the name:

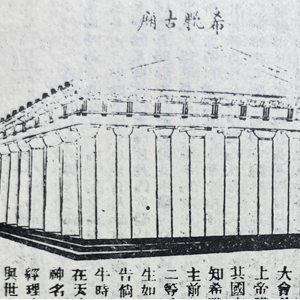

“The so-called Wuchi country is actually what was referred to as Hellas in antiquity. In Western languages, it is called Elishi, and the alternative names Elixi, Eleji or Elexiya, are phonetic permutations of the translation. … The establishment dates back, at its earliest, even to the times of Youyu [a legendary dynasty dated to the late 3rd millenium BC], and it is a place of an utterly cultured atmosphere. Before the Qin [221-207 BC], it was always known as Hellas, but by the Qin it came to be known as Greece (Wuchi). Although it is narrow and small, …, it is indeed the oldest of countries. … Since before Qin, its existence is vague, it cannot be checked, and even if there are records that can be examined, they are not trustworthy as proofs, and I ask to talk about its recent history. This country was once divided into 12 states, and when it was once attacked by Persia, the 12 states allied to resist it. Persia was defeated and retreated. It was only by Western Han times (206 BC – AD 18) that Rome conquered Europe by force and this country, too, came to be integrated into its territory. By the time when Rome had fallen, Turkey annihilated Eastern Rome, and took the whole of Greece with military force… In the 25th year of our dynasty’s Jiaqing era (1820), they drove out the officials installed by Turkey. Turkey levied troops and attacked Athens, its capital, but although they pressed hard, they were able to conquer it. England, Russia, and France heard of this, fortified it and supported Greece with troops, so that Turkey had no choice but to accept her declaration of independence. Although today’s Greece (Wuchi) is slightly different from what was before called Hellas (Xila), her scenic spots are the finest in the Western lands, her men and women are of most beautiful appearance, her libraries are also the most abundant in the West, and her palaces and monuments were the first models in the development of Western architecture.” (Shenbao, 15 May 1886)

Much of this narrative is literally taken from Xu Jiyu’s Yinghuan jilüe, albeit abbreviating (and hence conflating) parts of it. However, Xu had used Xila for “Greece” throughout, and did not argue that there was a difference between ancient and modern Greece, the first of which the Shenbao seems to be treating as semi-mythical.

So what exactly is this Wuchi identified with Greece? This is, again, a trickier question than it might seem, because Wuchi is not a very common name in ancient Chinese literature either. Outside of this set of articles, I have only been able to locate one reaction to this odd word usage and narrative, namely an English-language comment in the vol 15, no. 6 (1887, p. 376) of the China Review. The commentary showed astonishment about the Shenbao remark that Wuchi is a Western name, and offered two possible ways to understand it, both in reference to names found in ancient Chinese literature: A place called Wuchisan 烏遲散, and a country called Wucha 烏秅.The first, Wuchisan 烏遲散, appears in the Brief History of Wei (Weilüe 魏略), a work that goes back to the mid-3rd century. Although the Weilüe itself has been lost, the relevant chapter has survived as a quotation in Pei Songzhi’s 裴松之 (372-451) authoritative commentary to the Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo zhi 三國志), which Pei submitted to the emperor in 429. In 1885, the Sinologist Friedrich Hirth (1845-1927) had just suggested that Wuchisan was a rendering of the city name Alexandria. The phonetics of the reconstructed Old and Middle Chinese fit well (the <ch> in Wuchi, pronounced /ʈ͡ʂʰ/, is reconstructed to go back to old Chinese /l/), but the identification continues to be debated until today.

For the second hypothesis based on the name Wucha, the China Review found mentions in two entries of the Kangxi dictionary, a monumental standard work first published in 1716. One of these two entries indicate the tradition of reading Wucha as Yanna. The paper hypothesized that Yanna could refer to Yauna, the name commonly associated with Greece that ultimately goes back to the region of Ionia, and Wucha was a rendering of the ethnonym Achaeans.

However, the Kangxi dictionary contains another entry not mentioned in the China Review which brings us closer to the answer. The entry on the Chinese character Kun 崐 (used to write the mythological mountain Kunlun) cites the following example:

When Zhang Qian of the Han crossed the Western Sea, he reached the land of Daqin. To the west of Daqin lies the country of Wuchi, and further west of Wuchi, there is said to be another sea. On the shore of the Western Sea lies Small Kunlun, rising ten thousand ren in height, with a length of eight hundred li on each side.

This passage can be variously found in commentary literature discussing references to the “Western Sea” or Kunlun.[2] The commentaries point to literature from the 3rd century AD, most notably Zhang Hua’s (232-300) Treatise on diverse things (Bowuzhi). The authenticity of the Bowuzhi is a highly controversial point of discussion in Sinological debate. The passage is included in many modern editions of the Bowuzhi, but the prestigious critical edition at Zhonghua shuju holds that the second and third sentences are later interpolations. But apart from the question of textual authenticity, the Bowuzhi’s ‘information is somewhat wild and unhistorical’ (Leslie & Gardiner 1996, 94), and ‘fiction and reality is broadly mixed’ (Hoppál 2019, 69) therein. The cited passage, too, is ahistorical and ‘goes counter to all other sources’ (Leslie & Gardiner 1996, 94).

The place name of Daqin mentioned in the passage, on the surface, is homonymous with the Chinese Qin Empire mentioned in the article, but it referred to a country in the West that occurs in a number of other sources and is often identified with the Roman Empire. Its exact interpretation is contested. Friedrich Hirth argued that it refers specifically to the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. As Edward Pulleyblank explains, ‘the Chinese conception of Da Qin was confused from the outset with ancient mythological notions about the far west,’ which is demonstrated by the mention of Small Kunlun in this text. Zhang Qian was an explorer of the 2nd century BC who spent nearly two decades on official missions in Central Asia. However, he neither mentioned Daqin nor reached Western Asia. Consequently, research has not attempted to interpret the name Wuchi. At any rate, it seems to be a variant of the oft-discussed Wuchisan controversially identified with Alexandria, which also has a significant number of other variants.

Be it as it may, the 19th century author at the Shenbao must have really done what he described in the article. He read Chinese literature trying to find out what was known about Greece in ancient China, trying to match the information he found in the Yinghuan jilüe with information he gathered from Chinese historical sources. Since he did not find any Chinese sources from high antiquity that mentioned Greece, he seems to be treating ancient Greece as vague and unexaminable. However, he came across the above passage and identified Wuchi with Greece, which indeed lies to the West of the Western Asian regions identified with Daqin. Consequently, the author seems to take this first mention of Wuchi in a Chinese-language source as the first proof of Greece’s historicity, and treats the whole Greek history thereafter as confirmed.

This short series of articles for Greece remained isolated. Except for that one puzzled contemporary note in the China Review, the name Wuchi has fallen into absolute obscurity. The name Xila – which had emerged out of a shift towards the translating conventions of a Protestant missionary, but matched well with 19th-century romanticism and historicism, was too dominant to be replaced.

Yet, in spite of their apparent eccentricity, it is worth remembering such minor footnotes of intellectual history. The Shenbao episode shows us in a peculiar way that 19th-century intellectuals did not simply take European narratives of its own history for granted, but subjected them to reinterpretations according to their own historiographical background. It is ironic that, while doubting the historicity of ancient Greece, the Shenbao compared its dating to a mythical Chinese polity, and used one of the least reliable sources from the pool of Chinese literature as a benchmark of historicity. Yet, by stating that the modern Greece of the news reports was not quite the same entity as the ancient Greece to which the origins of the Western world were credited, the Shenbao author also ended up making an argument against simplistic tales of historical continuity on the European side. At the same time as he was making Sinocentric assumptions, our author inadvertently anticipated more recent trends to overcome state-centric historiographical approaches. Thereby, this episode reminds us of the fragility of the basic categories that organize modern historical thinking.

Notes

[1] In Southern Min languages, the same combination of Chinese characters creates a pronunciation akin to Hia̍h-lia̍k-se or Hia̍h-lāi-se or similar, which could conceivably be a rendering of Hellas rather than of Greece. However, this possibility is less likely, since Li was not native of a Southern Min area, and other transcriptions in the book also stem from English. Wei Wei 韋巍 mentions this secondary possibility in p. 139, fn. 4, of their article.

[2] The name Wuchi 烏遲 is often written as Niaochi 鳥遲, given the graphic similarity of Wu 烏 with Niao 鳥.

References

Aleni, Giulio [Ai Rulüe 艾儒略]. Zhifang Waiji 職方外紀 [Records of the lands beyond the imperial administration]. 5 jüan. Shoushange congshu 守山閣叢書. 1844 (1623).

‘Dianyin yiyao’ 電音譯要 [Essential translations of telegrams]. Shenbao. 12 May 1886.

Hoppál, Krisztina. ‘Chinese Historical Records and Sino-Roman Relations: A Critical Approach to Understand Problems on the Chinese Reception of the Roman Empire.’ Res Antiquitatis 1 (2019): 63 – 81.

Leslie, D. D., and Gardiner, K. H. J. The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources. Roma: Bardi, 1996.

‘Lun Wuchi-guo yongbing yuanqi’ 論烏遲國用兵原起 [On the origins of Greece’s use of military force]. Shenbao. 15 May 1886.

‘Notes and Queries.’ The China review, or, Notes and queries on the Far East 15 (1886/87): 366–77.

Pulleyblank, Edwin G. ‘The Roman Empire as Known to Han China.’ Review of The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources, by D. D. Leslie and K. H. J. Gardiner. Journal of the American Oriental Society 119, no. 1 (1999): 71–79.

Renger, Almut-Barbara, and Xin Fan, eds. Reception of Greek and Roman Antiquity in East Asia Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018.

Wang Wenhua 王文華. ‘Xila guoming hanyi tanyuan’ 希臘國名漢譯探源 [An exploration of the Chinese translation of the name for the country of Greece]. Fanyijie 翻译界, no. 1 (2019): 113–26.

Wei Wei 韋巍. ‘Dao-Xian shiqi xiyang shidi lunshu zhong di “Xila” wenming xingxiang yanbian’ 道咸時期西洋史地論述中的“希臘”文明形象演變 [The evolution of the image of ‘Greek’ civilization in the discourse about Western history and geography during the Daoguang and Xianfeng eras]. Guangdong shehui kexue 廣東社會科學, no. 6 (2022): 135–48.

Xila-guo shilüe希臘國史略 [Brief history of Greece]. Dong xi yang kao meiyue tongji zhuan東西洋考每月統記傳, no. 1 (wuxu 戊戌 [1838]): 312–14.

Xila-guo shi 希臘國史 [History of Greece]. Dong xi yang kao meiyue tongji zhuan 東西洋考每月統記傳, no. 2 (wuxu 戊戌 [1838]): 326–27.

Zhang Hua張華, Bowuzhi jiaozheng 博物志校正 [Treatise on diverse things, critical edition]. Edited by Fan Ning 范寧. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980.