In a play first performed in Calcutta in 1911, at the height of anticolonial Indian agitation against the British Empire, a Greek princess, Helen, daughter of Seleucus I Nicator, announced her marriage to the Indian king Chandragupta Maurya:

“Herodotus and Vyasa, Socrates and Buddha, Achilles and Bhishma, Pantheon and Purana have become one! […] By this marriage, Orient and Occident, ocean and firmament, heaven and earth, this world and the next, have completely merged into each other.” (Roy 1924, 153).

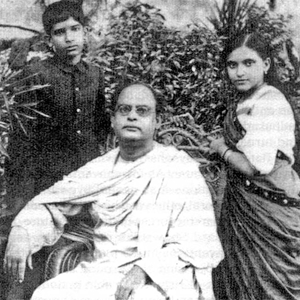

The playwright was none other than the militant-nationalist Bengali dramatist Dwijendralal Roy (1863-1913). For Indians like Roy, as indeed for others in the Islamic world or China, ancient Greece and Rome were part and parcel of their cultural inheritance. They encountered these civilizations through sculpture and architecture, through books, through travels. Over the past decades, historians have investigated how European imperialists engaged with the legacy of ancient Greece and Rome while establishing their rule across Asia and Africa. But we know relatively little about how non-Western populations, including subaltern actors like women and Indigenous communities, deployed Greece and Rome in the formation of their own politics. This series of blogposts, curated by Milinda Banerjee with help from Alok Oak, focuses on a varied spectrum of actors from South, East, and West Asia, in order to discover and describe this powerful inheritance.

For some Asians, Greece and (even more so) Rome were progenitors of European imperialism, but for many others, they were considered sibling civilizations. Greek and Roman gods, rulers, artists, philosophers, and public spheres supposedly resembled, or were at least comparable to, their Asian counterparts. Many Asian intellectuals and politicians pointed to these similarities and commensurabilities in order to challenge European colonialism. They were convinced that European and Asian societies evolved from a shared and common Eurasian landscape. The implication, stated with greater or lesser clarity depending on the specific actor, was that with the inevitable demise of modern European empires, these societies would once more converse with each other on a plane of civilizational equality.

In the aftermath of decolonization, postcolonial Asians continued to invoke Greece and Rome—often now to challenge the postcolonial state and ruling classes in the cause of advancing subaltern rights and dignity. Thus, the figure of Antigone could easily speak to popular resistance against postcolonial state sovereignty, as in the 1975 Antigone in Marathi, by Shriram Lagoo (1927-2019), and the 1986 Manipuri version of the same play by Ratan Thiyam (b. 1948). Both these Antigone‘s drew on the ancient play’s modern French reconstruction by Jean Anouilh (1944).

Ultimately, Greece and Rome were just terribly good to think with—they enriched and expanded Asian discussions on empire, democracy, gender, religion, and a whole range of other themes. As prophecies about planetary unity go, Dwijendralal Roy’s prognostication was over-optimistic at best. But in our present age of radical cultural fracture as well as hybridity, it may well be worth investigating as to why Asian elites and subalterns have so insistently conjured the spirits of Greco-Roman antiquity, and how such quasi-liturgical invocations have exploded modern worlds of politics and social imagination.

References:

Roy, Dwijendralal. 1924. Chandragupta. Calcutta: Gurudas Chattopadhyay and Sons.

Meet the Takeover Editorial Team

Milinda Banerjee is Lecturer in Modern History at the University of St Andrews.

Last summer, my wife and I travelled down the Aegean coast of Anatolia for my birthday. In some ways, the journey had the flavour of a nostos. My mother named me after a 2nd c. BCE Indo-Greek king Menander who had philosophically engaged with Buddhism, leading to his name being rendered in Pali as Milinda. My father would read stories from the Iliad and Odyssey to entice me to finish up breakfast before I headed for school. He would point out similarities between Greek gods and Indian ones, wryly observing how Greek and Indian heroes similarly behaved and misbehaved. And now I was finally in Troy in person! I had to videocall my parents in Calcutta to show them the sites.

Alok Oak is a Postdoctoral Fellow at IASH, University of Edinburgh.

The port-city of Mumbai, where I was born and raised, had trade relations with ancient Rome. My early introduction to Roman civilisation was during our annual school-trips to a local museum where we were shown Roman coins dating back to the 2nd -3rd century CE. But these trips served no particular purpose other than catering to the general curiosity of a school-going child. It was a chance encounter with two books during my teenage years — Albert Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus and Sudhir Kakar’s criticism of the supposed universality in the Freudian Oedipal complex — which pulled me into Greco-Roman myths and their Indian counterparts, while complicating my way of looking at the world.