This post is by Dr Maya Feile Tomes, Lorna Close Lecturer in Spanish at Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, and Affiliated Lecturer in Classics, Cambridge.

When can a fledgling or ‘emergent’ field be deemed to have ‘emerged’? In the Anglophone world, the classical traditions of Ibero-America have been slated as up-and-coming—often even as the next big thing—for the past several years now. I myself have been involved in the field for somewhat over a decade, from my first forays as a student to my first full-time position today, and the field has been classed as ‘emergent’ that entire time.

But there are perhaps signs that things are changing. Last year alone saw the publication of three stand-alone Anglophone volumes: Germán Campos Muñoz’ The Classics in South America (Bloomsbury), Stuart McManus’ Empire of Eloquence: The Classical Rhetorical Tradition in Colonial Latin America and the Iberian World (CUP), and the co-edited Brill’s Companion to Classics in the Early Americas (for which I am co-responsible). These join other key recent titles such as—to name just three more—Rosa Andújar & Konstantinos P. Nikoloutsos’s Greeks and Romans on the Latin American Stage (2020), Andrew Laird & Nicola Miller’s Antiquities and Classical Traditions in Latin America (2018), and Laura Jansen’s Borges’ Classics: Global Encounters with the Graeco-Roman Past (2018), while Andrew Laird’s much anticipated Aztec Latin: Renaissance Learning and Nahuatl Traditions in Early Colonial Mexico (OUP, forthcoming) will be hitting bookshelves shortly. The wonderful blogposts offered here in this Hespérides CRSN series over the past few months likewise attest to the mind-boggling vibrance, wealth, and diversity of modes of engagement with Greco-Roman material in the Ibero-American region across a multi-hundred-year period. Where earlier surveys of the field tended to circle around the same select but inevitably only small set of seminal titles, the panorama is now looking distinctly more populated. Indeed, looking again at this list, might one say that something of a critical mass has now been reached? Can we declare the field of Latin American classical to be out of its chrysalis once and for all?

It is difficult to answer these questions, of course, not least because history has a way of proving pronouncements about the state of the discipline—or anything for that matter—wrong. But perhaps we can at least take a moment here to consider the problem with allowing Latin American classical study to remain caught in its up-and-coming time warp and failing to acknowledge that the field is now something other than merely niche or brand new: ever more scholars across the world are actively working, permanent faculty appointments are being made, research networks founded, and so on. After all, for as long as the area continues to be treated on the old pattern, its scholars will in turn remain forever condemned to a labour of endless explication. Every Latin American classics scholar I know has a well-worn speech which they are able to trot out on demand, rehearsing the key dates and coordinates of the field and, yes, the genuine quality (whatever that means) and interest of the material in question. Every chapter, book and article published begins with a version of the same. Scholars of Ibero-American Classics do not have the same luxury as scholars of, say, Republican Rome or Renaissance Italy, who can simply take a certain core level of familiarity for granted and jump right in.

For obvious reasons, the need to keep (re-)establishing the existence and contours of the field is both tiring and ultimately counterproductive, partly because it may come across unhelpfully as special pleading, and not least because it also simply takes up a lot of space and time: having to begin each piece with the requisite potted history can leave little room to go on to say much else. Worse, it is often the case that, in their efforts to impress the ¡exciting! nature of the field upon their reader or interlocutor, scholars of the field may find themselves lapsing into the rhetoric of the extraordinary, which in turn runs the risk of exoticisation: the breathtaking fact of classical traces in early Ibero-America, the weird and wonderful corners of the regions to which Greco-Roman materials arrived by such staggeringly early dates, the remarkable range of cultural production that arose as a result. My use of the term ‘mindboggling’ in the previous paragraph is just such an example.

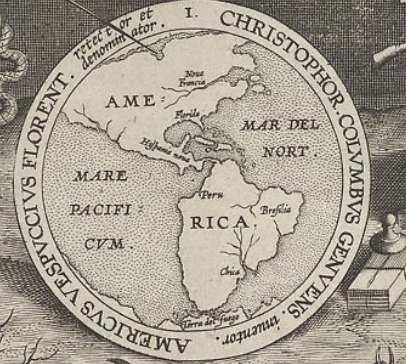

Moreover (as is certainly the case here), this is all very much at odds with how most scholars in the field would actually wish to see the subject matter treated, particularly as it is frankly at variance with the bald facts of the matter: after all, Greco-Roman material did not come to the Americas by the sort of miracle or osmosis that would be the cause for excitable exclamation but by the only too real, eminently well documented mechanisms of brutalising European invasion and colonialism after 1492. Virgil and friends were being read in the classrooms of sixteenth-century Mexico because Europeans mandated it. Epic poetry began to be composed from Cuba to Chile because that’s the form that Europeans insisted high literature took. Latin was taught because it was the language of the educational system and Catholic Church that Europeans were in the business of imposing across the region throughout this period. And so on. And so forth. Is it really for scholars of the transatlantic classical encounter to have to rehearse the history of a whole hemisphere as if it were a well-kept secret? Can the entire colonial history of the region really still constitute a subject of such surprise? And must these basic facts continue to come at the expense of the far more interesting question of what then happened next, beyond the initial European-imposed paradigm?

In terms of our own next steps as scholars today: we cannot say, of course, where things will go from here or how future intellectual historians will parse the vicissitudes of this early-mid C21st moment for our discipline. Many other important things are going on in the field, too, and will interact intersectionally with the questions that concern us here. But hopefully we may be on the cusp of something of a sea-change at least in terms of the surprise factor. Certainly there are clear practical reasons for optimism in this regard. After all, as mentioned at the start, there is now a fantastic body of accessible work to which interested readers can be usefully directed for further information and contextualisation. The burden of explication no longer rests with individual scholars alone but has been devolved onto this robust and ever-expanding body of scholarship which can be readily consulted by all. This in turn frees scholars up to conduct research, think thoughts, write pieces, give talks, prepare grant applications, etc., with the time and energy which will thus revert to them. In other words, the critical mass of scholarship now available serves, among other things, a very key practical purpose. And so it will be, if perhaps not ¡exciting! exactly, then certainly still exciting in its own way to see what happens next.