This post is written by Shruti Rajgopal, a final year PhD student at the school of History, University College Cork, Ireland

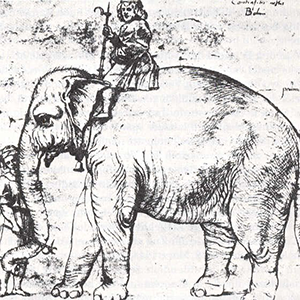

Wildlife from Asia, especially from India, has stirred fascination among Europeans since Greco-Roman times. During the Renaissance, European writers made frequent reference to classical Latin descriptions of elephants. Although it was used in the Middle Ages, a revived interest in Latin is visible from the early 1400s as an attempt to achieve linguistic uniformity concerning style and syntax.[1] Not only this, but classical texts were viewed by early modern Europeans as reservoirs of reliable references to various topics. This gave rise to the curriculum of the studia humanitatis, where Europeans were trained in classical Latin.[2] They emulated and imitated classical Latin authors such as Cicero and Vergil.[3] As a result, Europeans began to rediscover and conceive of their civic responsibilities by means of Latin texts.[4] As voyages to distant parts of the world became more prevalent, early modern Europeans began to use Latin texts to describe their experiences and also to differentiate themselves from the groups of people they encountered in these areas.[5] Furthermore, Marco Polo’s travel adventure (1271-1295) increased European interest in establishing cultural encounters with different parts of the east.[6] Marco Polo’s writing, combined with Greco-Roman conceptualisations of these places, seemed to create more realistic descriptions of distant landscapes. Travel literature from the fifteenth century onwards thus began to include complex details of people and the wildlife found in the east — India in particular.

Travel narratives written in Latin from the fifteenth and sixteenth century enabled the dissemination of knowledge of voyages to a greater audience, since the classical Latin language permitted uniformity of description, on account of the growing importance of studia, in contrast to vernacular descriptions.[7] Latin descriptions outlined characteristic details of India, which included accounts of the wildlife. For this reason, Pliny the Elder’s description of elephants dominated the perception among early modern intellectuals of this pachyderm. Although not always the central focus of the text, Neo-Latin descriptions often include details of elephants, echoing or emending Roman descriptions.

One of the first Neo-Latin descriptions of India was by a man called Poggio Bracciolini (De varietate fortunae, 1448). From his 15th century monograph to much later letters, written by Jesuits, each Latin text about India introduces elephants with reference to Pliny’s descriptions of them.[8] In this post, I will give an example or two of these descriptions from Poggio Bracciolini’s “India Recognita” (book four of De varietate fortunae) and Archangelus Madrignanus’s Latin translation of the Italian Itinerario by Ludovico Varthema.[9] Their reference to classical scholarship distinguishes them from the groups they encountered, since use of classical Latin associated them with the Roman world. Such a marked association fed into hierarchies of power and cultural value, giving rise to notions of colonialism from the fifteenth century onwards.

Poggio

Poggio’s “India Recognita,” was based on Nicolò de Conti’s (1395 -1469) journey to the east. Poggio describes Conti’s travel narrative which includes ethnography and descriptions of wildlife, and in particular elephants in the east, as Poggio described.[10]

Although brief, Poggio’s description of elephants is informative. His account demonstrates an engagement with classical texts, and at the same time responds to debates regarding language in Europe which were ongoing during this period.[11] There are two passages where he recalls Pliny’s description – the first one outlines the method by which elephants are trapped, tamed, and used in battles, and in the second instance he tells of its fraught relationship with the rhinoceros.[12]

In the first passage, Poggio directly cites Pliny and suggests that Conti confirms the details given by the classical author.[13] Furthermore, Poggio explains how ‘elephants react when javelins are thrown at their feet, which they instantly catch, to protect those riding on them.’[14] Similarly, Pliny describes the use of darts/javelins ‘thrown at their feet’ to draw their attention, when they are ‘taken for their tusks.’[15] Through this example, both Poggio and Pliny explain and reflect on elephants’ intelligence and their reaction to external elements. Although Poggio does not elaborate on or directly refer to Pliny, his extract on them ‘catching javelins’ refers to their quick responses and how they grab their attention through this act. In the context of nourishment provided to elephants, while Pliny explains that they are fed ‘barley juice to tame them,’ Poggio mentions that ‘rice and butter [are] fed to the domesticated [elephants],’ whereas those in the wild ‘feed on herbs and fruits.’[16] Poggio’s description aids his reader’s understanding by referring to details mentioned in the Historia Naturalis. The curriculum of the studia ensured training in classical texts, and readers trained by this method would have likely recognised Poggio’s reference to Pliny and his description of elephants.[17]

Poggio also, after Pliny, calls attention to the elephant’s conflict with the rhinoceros. Like Pliny, Poggio tells the reader that ‘a rhinoceros waged war against them [elephants].’[18] Years later, the Jesuit scholar Giovanni Pietro Maffei explained – in his Historiarum Indicarum Libri XVI (1588) – the hostility between the two species.[19] Here, Poggio does not give the complete context of the rivalry between the two creatures. He only mentions the same information narrated by Pliny, when he introduces rhinoceros in his “India Recognita.” Hence, Poggio does not reproduce the entire context, considering he is writing Conti’s observation. However, he narrates details of each species by reminding readers of their own classical understanding and descriptions of the same.

Madrignanus

Like Poggio, Archangelus Madrignanus (d.1529) also imparts similar details about elephants. In 1511 Madrignanus translated into Latin the popular Italian travel narrative by Ludovico Varthema. Commissioned by and dedicated to Cardinal Bernardino Carvajal (1456-1523), Madrignanus’s Latin translation made the Italian text accessible to a wider audience.[20] Furthermore, it showcases Madrignanus’s humanistic training through classical references.[21] Based on Varthema’s travel adventure to the east, Madrignanus outlines elephants as seen by the former in Cambay and various parts of south India.[22]

We are first introduced to elephants in the Cambay region of India in book one of Madrignanus’s Itinerario. He explains how ‘the elephants kneel, venerating the sultan.’[23] This example explains their posture. There are a few more extracts where Madrignanus describes their body and compares them with pigs and buffaloes.[24] Madrignanus’s translation is also a clear reference to Varthema’s visit, who is keener on illustrating his adventures through different parts of the east. As I have not found references to the sources that Madrignanus may have referred to, I cannot suggest whether he may have been influenced by Aristotle. Indeed, Aristotle described ‘how elephants bend their hind legs just like man’ in his Historia Animalium.[25] Trained in classical studies, Madrignanus does not directly refer to classical descriptions of elephants given by Aristotle. Although both the Italian and the Latin texts do not describe ‘hind legs,’ their reference to kneeling allows the reader to recall the Greek author. Aristotle further continues to explore the parts of this pachyderm in Book II of his Historia Animalium. What is more direct is Madrignanus’s reference to Pliny – in particular his remark on their docility.[26] Additionally, he echoes Pliny when he calls their trunk a hand (manum).[27] As seen from the above examples, descriptions by Pliny and Aristotle depict elephants in a humanising manner. Clearly, from his translation of trunks, even Madrignanus seems to describe and compare elephants with man. This will be clearer through the following example when he outlines how elephants mate. In addition to this, unlike Pliny, Madrignanus suggests that the female was wilder than the male. Therefore, as suggested before, not only do these Neo-Latin texts attest to their own classical understanding of these details, but they also offer more realistic accounts of the wildlife.

Elephantine love

Another fascinating example in Madrignanus’s translation is the use of the term barrus when he narrates how elephants have sex.[28] His description of copulation, like that of trunk, draws elephants into similarity with humans.[29] Regarding sex, both Varthema and Madrignanus confirm Pliny’s note that ‘elephants copulate in secrecy.’[30] What is also of significance in this example is his use of barrus which is found only once, although Varthema’s Italian uses no alternative for leophante. Reference to ‘barrus’ is found in Horace’s Epode 12, which is then examined by Porphyrio, who wrote a commentary on Horace’s Epodes and offers clarification on ‘barrus’ and its wider reference.[31] While Horace’s Epode 12 elaborates on sexual relations, Porphyrio’s comment and his influence on the renaissance translation can be easily traced.[32] Porphyrio not only explains, ‘elephants are called barros, as the voice of elephants is called barritus,’ but also further expands the poet’s understanding of the manner of copulation as ‘averse coire (turned backwards)’; the same phrase is found in Madrignanus, however, as a correction to this detail.[33] Although Madrignanus echoes Porphyrio, he also emends details in this passage to highlight, like Varthema, the comparison of elephants and humans. Therefore, the term might seem like a strange choice made by the translator, however, to a renaissance reader, the intertextuality and reference to copulation based on Horace and Porphyrio would not be lost. His choice of ‘barrus,’ further demonstrates his copia verborum, which means ‘abundance of words’, and was a facet of the studia Renaissance training, once again articulating a response to concurrent language debates in Europe.[34]

The translations by both Poggio and Madrignanus conform, therefore, to classical norms of Latin descriptions of elephants. Nevertheless, their knowledge goes beyond what was offered in antiquity. Neo-Latin literature engages with classical literature, but also emends it with reference to more recently observed nature in the accounts of travel writers. Beyond travel writers, more and more missionaries went to these areas and wrote about native species of plants and animals, aiding awareness among western readers. [35] The association of elephants with India is one of the few features that enhanced the western reader’s understanding of the subcontinent’s diverse wildlife.

References

[1] Celenza, Christopher. 2018 The Intellectual World of the Italian Renaissance, (New York; Cambridge University Press). pp. 1-44; Mommsen. T. 1942 “Petrarch’s Conception of the ‘Dark Ages'”, Speculum, vol.17, No.2, p. 226-242.

[2] Black, Robert. 2001 Humanism and education in medieval and Renaissance Italy: tradition and innovation in Latin schools from the twelfth to the fifteenth century (Cambridge University Press).

[3] Kristeller, Paul Oskar. 1969 Studies in the renaissance thought and letters (Roma: Edizioni di storia e letteratura).

[4] Grendler, Paul F. 2014 “Jesuit Schools in Europe. A Historiographical Essay,” Journal of Jesuit Studies, pp. 7-25.

[5] Celenza, Christopher. 2004 The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanists, Historians and Latin’s legacy, (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press), Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. 2017 Europe’s India- Words, People, Empires 1500-1800 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: Harvard University Press). Subrahmanyam, Alam. 2009, “Frank Disputations: Catholics and Muslims in the Court of Jahangir (1608-1611)”, Indian Economic Social History Review, Vol.46, pp. 457-511.

[6] Marci Pauli Veneti, “Liber Tertius”, Historici fidelissimi juxta ac praestantissimi, de regionibus orientalibus (1671), pp. 128-167.

[7] See Curti, Elisa. 2013. “Bembo e la questione della lingua nel Cinquecento,” Griseldaonline – il portale di letteratura, University of Bologna, for language debates in Italy during this period; there were similar debates about the vernacular as well in Italy during this period. For further reading, Eskhult, Josef. 2018 “Vulgar Latin as an emergent concept in the Italian Renaissance (1435-1601): its ancient and medieval prehistory and its emergence and development in renaissance linguistic thought,” Journal of Latin Linguistics, Vol. 17, Iss.2, pp. 191-230.

[8] Poggio Bracciolini, “India Recognita”, De varietate fortunae (1723), ed. Josef Wicki, Documenta Indica, vol. I, Letter 6 (22/10/1545), Monumenta Historica Soc.Iesu, Romae (1948).

[9] Ludovico Varthema, Ludovici Patritii Romani Novvm Itinerarivm Aethiopiae: Aegipti: Vtrivsqve Arabiae: Persidis: Siriae: ac Indiae: Intra et Extra Gangem, tr.to Latin by Archangelus Madrignannus, (1511), pp. XXVIII-LX.

[10] Poggio mentions elephants in ‘Macinum,’ which has been recognised as the kingdom of Orissa by Fra Mauro. For further reference, Falchetta, Piero. 2006 Fra Mauro’s world map: with a commentary and translations of the inscriptions (Brepols), Venezia.

[11] Botley, Paul. 2004 Latin translation in the renaissance. The theory and practice of Leonardo Bruni, Giannozzo Manetti, Erasmus (CUP).

[12] India Recognita, p. 134.

[13] Here, he says ‘Conti’s observation of the manner in which elephants are taken coincides with what Pliny says,’ p. 132.

[14] India Recognita, p. 134.

[15] Pliny, Historia Naturalis, Book VIII, Ch. VIII.

[16] India Recognita, pp. 132-133, Pliny, Ch. VII.

[17] For Poggio’s text and its importance for intertextuality see Juncu, Meera. 2019 India in the Italian renaissance Visions of a Contemporary Pagan World 1300-1600.

[18] Poggio compares their body sizes and then explains that ‘a rhino wages war against elephants’ (my translation, Poggio, p. 134), whereas Pliny says, ‘another bred here to fight matches with an elephant,’ Ch. XXIX (trans. H. Rackham).

[19] Giovanni Pietro Maffei, Historiarum Indicarum libri XVI (Florence, 1589), p. 102.

[20] See Kristeller and Botley for further details on language debates during this period.

[21] Rossetti, Edoardo. 2017 “Visioni di riforma. Il cardinale Spagnolo Bernardino Lopez de Carvajal e le elite Milanesi nella crisi religiosa di primo Cinquecento (1492-1521), PhD. Thesis, University of Padua and Venice. Rossetti examines his political and ecclesiastical career.

[22] Madrignanus, Book I (1511), Chps. I, IX, X, XI.

[23] Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. II.

[24] The Itinerario does describe ‘female being smaller than a male,’ and comparisons with buffaloes and pigs to describe various features. Refer to Book I, Chp. X.

[25] Aristotle, Historia Animalium, Book II, trans. A. L. Peck (London: William Heinemann Ltd., Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965),78-79.

[26] Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. X, Pliny, Book VIII, Chp. I, III.

[27] Pliny, Book VIII, Chp. X. Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. X.

[28] Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. XI.

[29] Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. XI (dicunturque fere humanitus veneri operam dare).

[30] Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. XI, Pliny, Chp. V.

[31] Horace, Epodi, 12.1.

[32] Henderson, John. 1999 “Horace talks rough and dirty: No comment (Epodes 8 & 12), Scholia: Studies in Classical Antiquity, Vol. 8, Iss. 1, pp. 3-16.

[33] Porphyrio, Commentum in Horati Epodes, Madrignanus, Book I, Chp. XI.

[34] Gravelle, Sarah Stever. 1988 “The Latin-Vernacular question and humanist theory of language and culture,” Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 49, Iss. 3, pp. 367-386.

[35] Refer to the Documenta Indica series, and Latin texts such as Iacobus Bontius’s De medicina Indorum (1642)