This post is by Eduardo García-Molina,  a fourth-year graduate student in Classics at the University of Chicago. While currently writing his dissertation on communication and administration in the Seleukid Empire, he is also interested in the reception of the ancient cultures in Latin America with a particular emphasis on Cuba and Puerto Rico.

a fourth-year graduate student in Classics at the University of Chicago. While currently writing his dissertation on communication and administration in the Seleukid Empire, he is also interested in the reception of the ancient cultures in Latin America with a particular emphasis on Cuba and Puerto Rico.

No soy la bárbara de quien todos hablan. Un cuento que inventaron esos malditos griegos, pueblo orgulloso, autosuficiente, amenazante; vienen desde el norte, buscan el vellocino, dicen; […] Para ellos todo es bárbaro y a todo lo que no esté en su territorio le llaman bárbaro y se acercan melosos, ofreciéndoles caramelos a los niños bárbaros.

— Abelardo José Estorino López, “Medea Sueña Corinto” (2008)

I’m not the barbarian everyone talks about. A story invented by those damned Greeks, a haughty people, independent, menacing; they come from the north, they seek the fleece, they say; […] For them everything is barbaric and they call everything not in their territory barbaric and they approach with a honeyed disposition, offering sweets to the barbarian children. [1]

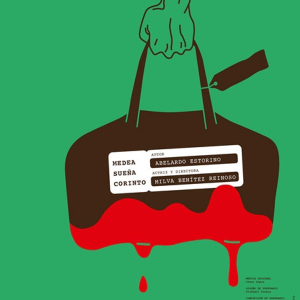

Medea has always been an alluring figure for playwrights, arguably most emblematised by Euripides’ (in)famous firebrand who “would rather stand behind a shield three times than give birth once” (ll. 250–251). Cuban playwright and director Abelardo José Estorino López (1925–2013) sought to engage with the character of Medea in an unabashedly Cuban context when he wrote “Medea sueña Corinto” (“Medea dreams of Corinth”). The play was first staged in 2008 with Estorino directing and later re-envisioned in 2013 by Milva Benítez Reinoso for the Teatro del Pueblo at the Sala Teatro Adolfo Llauradó in Havana. In an emotional monologue, Estorino’s Medea grapples with the actions and feelings that brought her to Corinth and her identity as an immigrant. Her optimistic vision of Corinth as a centre of civilisation and culture quickly crumbles; the stark realities of Greek prejudices and exploitation ultimately shattering the dream she held for herself and her children. Fixating on Medea’s creeping disenchantment, Estorino taps into the conflicting emotions of many immigrants who realise that underneath the dream of America lies an exploitative system that consumes all.

A peculiar aspect of this system is the use of labels and the appropriation of narratives. Estorino’s Medea is aware of past narratives of herself. She orders Euripides to come out of hiding and tell the audience the truth about her, glumly noting how her image has been warped by foreign authors. Speaking to the audience, she tries to justify herself as “a sweet, loving woman” whose history has been distorted by rapacious Greeks. These Greeks, in their hunt for resources like the golden fleece, are fascinated by the land and peoples they label “barbarian.” This sort of exoticisation and fetishisation of lands, bodies, and cultures is used by imperial powers to label, separate, and otherise. For Latin America, this process of tropicalisation has served to typify its people as the strange denizens of exotic lands: passionate, spiritual, violent, and hypersexual.

In Medea’s struggle to take control of her own narrative from foreign authors, Estorino presents a stark reminder of how stories of immigrants are frequently distorted and appropriated by non-immigrants. Immigration from Cuba has been frequently weaponised by Americans to underscore their own political views or to propagate the depiction of America as a land of promise, drowning out the stories and voices of the immigrants themselves. Medea consults other authors in the hope of helping her decision to follow Jason but finds nothing. Dismissing these books as reflections of their authors but not of herself, Medea proclaims she is heading to Corinth, “the emporium of wealth, money, and power.” The audience shares her hope to break free of the cycle of misrepresentation, but one cannot help but feel a sense of unease as Medea joyfully dances to a mixture of Greek and North American music before departing.

During the play, Medea’s long white dress intermittently changes to incorporate vibrant streaks of red and blue fabric. The first lines of the play reveal that these pieces of fabric come from the coat of Medea’s doomed daughter. Both the costuming and the musical cue serve as audiovisual signals for the audience that further blur the line between Medea’s Corinth and Estorino’s America. In Corinth, Medea struggles to acclimate; her Greek is still clunky and Jason has grown increasingly distant after the birth of their children. Mockingly parroting the voice of Creon, she reveals Jason is to wed Creusa whom the entire “civilised world” talks about. For Medea, the dream of Corinth devolves into a nightmare as she finds herself misled by false promises from Jason, alone in a foreign land, and on the verge of being deprived of her children by the state. In a final act of defiance, she presents the tainted wedding gown to her children to deliver to Creusa. Unfortunately, the uncontrollable inferno caused by the flammable dress consumes her children as well. The final lines resemble a dirge as Medea laments the loss of children in a land that was once full of promise. The dream of Corinth, however, ultimately revealed itself to be a nightmare that envelops all until nothing remains but “cenizas, cenizas, cenizas” (“ashes, ashes, ashes”).

[1] All translations by García-Molina.