The first post in the Realigning Reception blog series is written by Leo Kershaw, a second-year PhD student at the University of Oxford writing his dissertation on receptions of Medea in South Africa. He is interested in the reception of Greek tragedy, postcolonial and decolonial theory, and the intersections of race, class, and gender, and is contributing a chapter on Herakles outside the Western canon for a forthcoming Blackwell-Wiley handbook to Herakles (2024).

‘Beware of the neo-colonial wolf’: World Reception, Universality, and Decolonising the Academy

‘Global’ classical reception cannot easily be defined, and in fact, trying to do so may be problematic. When invoked in European higher education curricula, the category of ‘world literature’ often insinuates a false opposition between ‘the West’ and the global ‘other’. In their recent volume Greeks and Romans on the Latin American Stage, Rosa Andújar and Konstantinos Nikoloutsos problematise the very concept of regional postcolonialism, demonstrating how attempts to draw generalising conclusions about a vast and diverse region like ‘Latin America’ erroneously assimilate important differences, creating an essentialised ‘hybrid’ which is easier for the West to digest. Propagating these homogenised, regional identities consequently privileges a colonial, ‘whitewashed European picture of the region’ (Andújar and Nikoloutsos 2020, 2).

How can we go about theorising something as vast and complex as ‘global’ reception without reinforcing colonial ideologies and systems of knowledge, but with an actively decolonial agenda? Some key questions to consider include:

- What counts as ‘classical antiquity’? What might be problematic about our definitions?

- Is it possible to disentangle classics from colonialism? Should we seek to do so?

- How do we responsibly and ethically practise reception in the field of postcolonial classics? How do we decolonise the academy?

Decolonisation, rudimentarily defined, is the unpicking of the colonialism that has been woven into our cultural, institutional, educational, political, and social infrastructures. Decolonisation criticises and breaks down colonial pasts and presents, and disentangles the subject from its colonial baggage, while recognising its damaging impact. It means being uncomfortable in our confrontation with colonialism, and working through that uncomfortableness, rather than looking away from it as something that is now behind us. While we may be living in a postcolonial world, the legacies of colonialism remain. The ‘post-’ of postcolonialism is not simply a temporal prefix, but an insistence upon critical examination of colonialism’s legacy (Quayson 2020, 4). We cannot, therefore, have a truly postcolonial academy without decolonisation.

To be a decolonising scholar is to recognise what Patrice Rankine calls the ‘cultural baggage’ that classics carries with it, namely, modern realities of slavery, race, colonialism, and their impacts after global abolition, emancipation, and ‘any declaration of a post-racial period’ (Rankine 2019, 345). Herein lies a methodological concern for those of us studying topics like ancient slavery, articulated by Dal-el Padilla Peralta: ‘how to devise modes of disciplinarity and discourse that do not intentionally or unwittingly reinscribe domination[?]’ (Padilla Peralta 2018, 1). In a field so heavily saturated in white supremacy, even those with the best intentions might end up ‘authorising and buttressing exploitation, by furnishing our students and colleagues with a language and worldview that effaces or occludes certain forms of human suffering’ (Padilla Peralta 2018, 2). The academic realm of reception itself has even been understood as a form of colonisation, in that an ‘other’ — the ancient material — is subjected to the all‐defining points of view of the appropriators or ‘receivers’ (Kaufmann 2006, 192). The close association between classical studies and colonialism has, in practice, resulted in a prevailing sense of hostility to classics in regions like the Caribbean and South Africa, where engaging with the field and all its colonial baggage is viewed as incompatible with celebrating indigenous culture, and as acquiescing to Westernisation (Greenwood 2009, 238).

In light of these complex issues, how do we decolonise the academy? It is important to note that decolonisation is not an achieved state, but an ongoing process. Achille Mbembe argues, à la Frantz Fanon, that decolonisation reflects ‘the permanent possibility of the emergence of the not-yet. […] [T]he possibility of a different type of being, a different type of time, […] the possibility of reconstituting the human after humanism’s complicity with colonial racism’ (Mbembe 2019, 54). Decolonisation is thus a process of becoming, which inevitably remains incomplete.

An important point in the history of the decolonisation movement is the work of the Caribbean poet and theorist Aimé Césaire. In 1939 he published the Notebook on the Return to My Native Land, a hugely influential text in the development of the Négritude movement, which uses cultural memory as a form of resistance against racist colonial ideology, and is itself an exploration of the decolonising consciousness. Négritude has had an immeasurable impact on Caribbean literature, decolonisation movements across Africa, and the affirmation of Black identity. Césaire was writing, as he puts it, in a century of ‘exacerbated Eurocentrism, a fantastic ethnocentrism, that enjoyed a guiltless conscience’ (Césaire 2008, 992). The ostensible superiority of European civilisation and its ‘universal vocation’ went unquestioned; in other words, Western exceptionalism, which weaponised the classical to bolster its authority, was interiorised by coloniser and colonised alike.

Césaire may have been writing almost a century ago, but his words are no less relevant today. In many ways, classics is still awaiting decolonisation. Globally, there is an ambivalence between classics and postcolonialism. This tension lies in the rejection of classics as tainted by empire and colonialism, and in the countervailing appropriation of classics as a source and site of cultural resistance (Greenwood 2009, 252). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European colonisers appropriated the civilisational authority of Greece and Rome and aligned these civilisations with modern European imperialism (Vasunia 2013, 4). Graeco-Roman classical texts formed part of the ‘the apparatus of colonialism’, often embedded in educational curricula (Goff and Simpson 2007, 1). During the colonial periods, the dissemination of the classical was, therefore, predominantly a process of unequal exchange.

In the contemporary postcolony, the transculturation of the classical disrupts this hierarchical dynamic, and cross-cultural elements become ‘entangled’ through the process of reception (Cole 2020, 26). Global postcolonial transculturation breaks down into several stages, the first of which is the deconstruction of a so-called ‘foreign’ text; then, the rearrangement of the deconstructed text using codes ‘inscribed in the indigenous culture’; and finally, ‘the disappearance of the model into the next text or technique within its culture’ (Weber 1991, 34). Amongst African theorists, such reception is known as ‘post-Afrocentricism’ or ‘African interculturalism’. In Scars of Conquest/Masks of Resistance, Tejumola Olaniyan notes three competing discursive formations: Eurocentric, Afrocentric, and post-Afrocentric, which ‘subverts both the Eurocentric and the Afrocentric while refining and advancing the aims of the latter’ (Olaniyan 1995, 11). The post-Afrocentric approach seeks not only different representation of the cultural self, but questions the representation of difference. Post-Afrocentricism takes as its subject the issues which legitimise or problematise intercultural fusion of European and African cultures, or in Biodun Jeyifo’s words, ‘the complex relations of unequal exchange’ (Jeyifo 2002, 158).

This raises the question: to what extent, and for whom, is the syncretisation of Graeco-Roman traditions and contemporary postcolonial cultures desirable? The Nigerian playwright Femi Osofisan recently explained that if the original context of his adaptations of Greek tragedy are forgotten by the receiving Yoruba audience — if they are not hyperconscious of the play’s multiculturalism — that is ideal (Osofisan, 2021). His intent, in writing Medaye (2021), is not to blend Greek and Yoruba cultures, but to deconstruct the Greek world view and rewrite Euripides’ Medea to recover the African world view. Osofisan views drama as a method for creating, and thereby metadramatically disrupting, history. This kind of decolonial reception offsets the hegemony of European classicism, offering a new, anti-colonial interpretation of the past and generating new paths for the field’s future.

The notion of dismantling the ancient worldview is underpinned by an important concern of decolonial theory, the concept of the universal. Certainly, there is something widely appealing in the Graeco-Roman classics which speaks to audiences across time and space. However, there is a danger in conflating this with the Western conceit of the ‘universal’. When the term ‘universal’ is invoked in the context of classics, it is often used as a synonym of ‘Western’ or, more dangerously, ‘Western civilisation’. The idea of Graeco-Roman antiquity as the origin of Western civilisation is a harmful myth that erases the important global connectivities that have existed since antiquity. Phiroze Vasunia, Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad, Francesca Orsini and Maddalena Italia demonstrate in their current project, Comparative Classics; Greece, Rome, India, how our perspective on Greece and Rome as the origin of the ‘universal’ collapses when we shift the epicentre of our study and reposition it, for example, on Sanskrit, Hindi, and Urdu literature (Vasunia, Ram-Prasad, Orsini and Italia 2021). This methodology of decentring Graeco-Roman antiquity is essential for decolonising the academy.

Many postcolonial scholars have argued that ‘universality’, in actuality, privileges Western texts and performances as being above cultural differences, or ‘acknowledges non-Western texts and performances not as equal and valid on their own merits but only in their integration into a Western framework’ (Wetmore 2002, 38). Importantly, European conceptions of the universal reach back to Graeco-Roman antiquity for justification: decolonial theorist Frantz Fanon, in fact, views the Greeks as the first ‘universalising’ imperialists, who sought to ‘Hellenize’ the Asian peoples they encountered (Fanon 1965, 8). ‘Universalism’ has been repeatedly denounced by Black decolonial theorists, including the prodigious Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka, who warns, ‘beware of the neo-colonial wolf, dressed in the sheep’s clothing of ‘universality’’ (Soyinka 1986, 408).

So, if we reject the concept of universality, where do we look instead to find terminology for a decolonial, global reception of classics? Emily Greenwood proposes the concept of the ‘omni-local’, a model which decentralises European classical receptions and is more attuned to the translatability and cultural mobility of Greek and Roman works (Greenwood 2013, 354). Unlike ‘universality’, omni-localism emphasises the ‘unpredictable circulation’ of art and ideas, in which ‘any given reception is ‘local’ in relation to every other reception, while together they form part of a larger whole through their connection with a single text or work of art’ (Greenwood 2013, 359). It is through this notion of connectivity, rather than universality, that ‘new avenues of exploration’ are created which ‘transcend a Eurocentric reading of the classics as the pillar of universal history’ (Bocchetti 2016, 8). We need, therefore, to understand the classics, and our position as classicists, as functioning at ‘nodal points’ within a vast field whose boundaries are permeable and ever-shifting (Güthenke and Holmes 2018, 58).

Global reception, therefore, cannot and perhaps should not be condensed into a single theoretical model. To attempt to do so is to risk homogenising or erasing important and nuanced differences that constitute the value of omni-local receptions. As classical remnants are deconstructed and reformed into post-, anti-, and decolonial works of reception, they ‘encourage us in the direction of a deeper understanding of our contemporary world’ (Rankine 2019, 346). The globalisation, rather than universalisation, of classical literature, as it is absorbed into different languages, cultures, and contexts, itself furthers the process of decolonisation, dispersing ‘any particular discourse’s claim to singular authority’ over the material, which Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins perceive as central to decolonisation (Gilbert and Tompkins 1996, 173). Indeed, as Justine McConnell argues, there is no ‘postcolonial response’ to works of antiquity, but rather, ‘a multitude of postcolonial and anticolonial responses that differ radically from each other’ (McConnell 2013, 3). The key to ‘world’ or postcolonial literature, therefore, is plurality and connectivity, rather than ‘universality’.

WORKS CITED

Andújar, Rosa and Nikoloutsos, Konstantinos P. 2020. Greeks and Romans on the Latin American Stage. London.

Bocchetti, Carla. 2016. ‘Global History, Geography and the Classics.’ In Global History, East Africa and the Classical Tradition. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est. Vol. 51: 7–20.

Césaire, Aimé in Rowell, Charles H. 2008. ‘IT IS THROUGH POETRY THAT ONE COPES WITH SOLITUDE*: An Interview with Aimé Césaire.’ Callaloo. Vol.31(4): 989–997.

Cole, Catherine. 2020. Performance and the Afterlives of Injustice. Dance and live art in contemporary South Africa and beyond. Michigan.

Fanon, Frantz. 1965. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Farrington, Constance. New York.

Gilbert, Helen and Tompkins, Joanne. 1996. Post-Colonial Drama: Theory, Practice, Politics. London; New York.

Goff, Barbara and Simpson, Michael. 2007. Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone, and Dramas of the African Diaspora. Oxford.

Greenwood, Emily. 2009. Afro-Greeks: Dialogues between Anglophone Caribbean Literature and Classics in the Twentieth Century. Oxford.

Greenwood, Emily. 2013. ‘Afterword: Omni-Local Classical Receptions.’ Classical Receptions Journal. Vol.5(3): 354–361.

Güthenke, Constanze and Holmes, Brooke. 2018. ‘Hyperinclusivity, Hypercanonicity, and the Future of the Field.’ In Formisano, Marco and Shuttleworth Kraus, Christina, eds. Marginality, Canonicity, Passion. Oxford: 57–73.

Jeyifo, Biodun. 2002. Modern African Drama: Backgrounds and Criticism. New York; London.

Kaufmann, Helen. 2006. ‘Decolonizing the Postcolonial Colonizers.’ In Martindale, Charles and Thomas, Richard, eds. Classics and the Uses of Reception. Oxford: 192–203.

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Out of the Dark Night. Essays on Decolonization. New York.

McConnell, Justine. 2013. Black Odysseys: The Homeric Odyssey in the African Diaspora since 1939. Oxford.

Olaniyan, Tejumola. 1995. Scars of Conquest/Masks of Resistance: The Invention of Cultural Identities in African, African-American, and Caribbean Drama. New York.

Osofisan, Femi. 2021. ‘Femi Osofisan (playwright and poet) in conversation – Ibadan/Reading/APGRD event.’ (1 November 2021) <https://youtu.be/PhLEV-l7Hmo>

Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2018. ‘The death of a discipline.’ SCS 2018: 1–5.

Quayson, Ato. 2020. Tragedy and Postcolonial Literature. Cambridge.

Rankine, Patrice. 2019: ‘The Classics, Race, and Community-Engaged or Public Scholarship.’ American Journal of Philology. Vol.140: 345–359.

Soyinka, Wole in Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 1986. ‘Race’, Writing, and Difference. Chicago; London.

Vasunia, Phiroze. 2013. The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford.

Vasunia, Phiroze; Ram-Prasad, Chakravarthi; Orsini, Francesca and Italia, Maddalena. 2021. ‘Decolonisation.’ APGRD Research Seminar: Receptions & Comparatisms. (8 November 2021) <https://youtu.be/rn-7LpQj2yQ>

Weber, Carl. 1991. ‘AC/TC: Currents of Theatrical Exchange.’ In Marranca, Bonnie and Dasgupta, Gautam, eds. Interculturalism and Performance: writings from PAJ. New York: 27–38.

Wetmore, Kevin J., Jr. 2002. The Athenian Sun in an African Sky. London.

FURTHER READING

Key reading on postcolonial and decolonial theory:

Césaire, Aimé. 2000. Discourse on Colonialism. Trans. Pinkham, Joan. Marlborough; New York.

Césaire, Aimé. 1995. Notebook of a Return to My Native Land. Trans. Rosello, Mireille and Pritchard, Annie. Newcastle upon Tyne.

Fanon, Frantz. 1965. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Constance Farrington. New York.

Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. California.

Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Out of the Dark Night. Essays on Decolonization. New York.

Quayson, Ato. 2021. Tragedy and Postcolonial Literature. Cambridge.

Thambinathan, Vivetha and Kinsella, Elizabeth Anne. 2021. ‘Decolonizing Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Creating Spaces for Transformative Praxis.’ International Journal of Qualitative Methods. Vol.(20): 1–9.

Studies on classics and postcolonial theory:

Goff, Barbara, ed. 2005. Classics and Colonialism. London.

Greenwood, Emily. 2013. ‘Afterword: Omni-Local Classical Receptions.’ Classical Receptions Journal. Vol.5(3): 354–361.

Kaufmann, Helen. 2006. ‘Decolonizing the Postcolonial Colonizers.’ In Martindale, Charles and Thomas, Richard, eds. Classics and the Uses of Reception. Oxford: 192–203.

Padilla Peralta, Dan-el. 2019. ‘The Future of Classics. Racial Equity and the Production of Knowledge.’ SCS 2019: 1–14.

Rankine, Patrice. 2019. ‘The Classics, Race, and Community-Engaged or Public Scholarship.’ American Journal of Philology. Vol.140: 345–359.

Postcolonial scholarship on global classical reception:

Andújar, Rosa and Nikoloutsos, Konstantinos P., eds. 2020. Greeks and Romans on the Latin American Stage. London.

Goff, Barbara and Simpson, Michael. 2007. Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone, and Dramas of the African Diaspora. Oxford.

Bosher, Kathryn; Macintosh, Fiona; McConnell, Justine and Rankine, Patrice, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Greek Drama in the Americas. Oxford.

Greenwood, Emily. 2009. Afro-Greeks: Dialogues between Anglophone Caribbean Literature and Classics in the Twentieth Century. Oxford.

Johnson, Marguerite, ed. 2021. Antipodean Antiquities: Classical Reception Down Under. London.

Malamud, Margaret. 2016. African Americans and the Classics: Antiquity, Abolition and Activism. London.

McConnell, Justine. 2013. Black Odysseys: The Homeric Odyssey in the African Diaspora since 1939. Oxford.

Moyer, Ian; Lecznar, Adam and Morse, Heidi, eds. 2020. Classicisms in the Black Atlantic. Oxford.

Rankine, Patrice. 2006. Ulysses in Black: Ralph Ellison, Classicism, and African American Literature. Wisconsin.

Richardson, Edmund, ed. 2019. Classics in Extremis. London.

Stephens, Susan A. and Vasunia, Phiroze, eds. 2010. Classics and National Cultures. Oxford.

Van Zyl Smit, Betine, ed. 2016. A Handbook to the Reception of Greek Drama. Chichester.

Vasunia, Phiroze. 2013. The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford.

Walters, Tracey Lorraine. 2007. African American Literature and the Classicist Tradition: Black Women Writers from Wheatley to Morrison. Basingstoke.

Wetmore, Kevin J., Jr. 2002. The Athenian Sun in an African Sky. London.

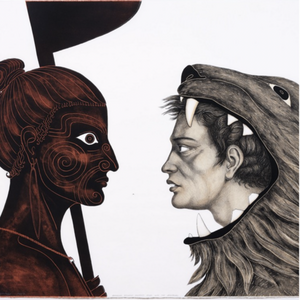

The image featured at the top of this post is Marian Maguire’s ‘Herakles discusses Boundary Issues with the Neighbours’ (lithograph, 2007). Image reproduced courtesy of the artist.