Homer in Cape Town: the sculptural assemblages of Charlayn von Solms

In February’s African takeover blogs, I (Dr Samantha Masters, Stellenbosch University) speak to Charlayn von Solms, a contemporary South African artist whose most recent sculptural projects present a fascinating creative intersection between contemporary art and Homeric poetry.

Charlayn’s technique is sculptural assemblage, and in her work she draws conscious comparisons between the physical process/manufacture of sculpture and the oral compositional techniques used by Homer (or poets like Homer). She draws on what she terms the iconography of Homer, but also generally, on iconography and forms from Greek antiquity, however her interpretations are metaphorical rather than literal and this makes the work complex and fascinating.

It was almost a year ago (and just before South Africa went into its COVID lockdown) that Charlayn von Solms’ book launch for A Homeric Catalogue of Shapes: The Iliad and Odyssey Seen Differently (Bloomsbury, 2020) and new exhibition Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25, took place at the Stellenbosch Town Hall during the Stellenbosch University Woordfees (Literary Festival).

SM: Can you briefly describe the concept behind Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25, the new exhibition, and its scope. And who is Powell?

CvS: To me, the catalogue format is a core part of oral poetry, and I’m very interested in how its narrative and aesthetic impact can become obscured within a literate context. Catalogues appear to place a larger interpretive burden on the audience than narrative does, but offers far greater scope for internal critique, commentary, and allusion (for example, see Benjamin Sammons The Art and Rhetoric of the Homeric Catalogue, Oxford University Press, 2010). Barry Powell identified a set of structural patterns underlying Homer’s most elaborate catalogue in “Word Patterns in the Catalogue of Ships (B 494-709): A Structural Analysis of Homeric Language.” Hermes, Vol. 106, No. 2 (1978), pp. 255-264). Powell sees these in purely structural terms, but I was curious whether any thematic similarities occurred within these patterns. I started with the pattern that contained the Pylian entry (number 11) as the story of Thamyris contained within it was clearly juxtaposed with the description of a muse-poet interaction in the invocation at the outset of the catalogue. The three other entries – 2, 20, and 25 – featured sets of brothers with famous fathers/grandfathers (Ares, Herakles, and Asclepius). Nestor therefore seemed out of place.

Enter Douglas Frame’s Hippota Nestor (Center for Hellenic Studies, 2009). Frame’s thesis is that Homer’s Nestor is what remains of a set of twins in the model of the Dioscuri. This specific structural pattern therefore offered an opportunity to explore the catalogue in terms of relationships between elements that are present and those that are absent, yet implied. So for example, Asclepius in the sculptural series alludes to the two references to Eurytos of Oikhalia in entries 11 and 25 through his epithet – Oichesthai (to be gone).

SM: So, like A Catalogue of Shapes, this artwork is one of reception of classical antiquity, but not only (or even mainly) of aesthetics, but instead of poetics. People may be curious about how you became interested in classical antiquity, and in particular Homeric poetry. Let’s start with aesthetics. Was classical art part of your Fine Art training at UCT?

CvS: Yes and no. I learnt a lot more about how classical art provoked a wide range of contradictory ideas and ideals, than of the actual artworks themselves. In high school in Pretoria in the late 80’s for example, our one short foray into Greek and Roman art was an uncritical rehashing of Winckelmann’s ideas: i.e. that art from the 5th century represented the apex of all human artistic achievement (apparently it was all downhill from there). Roman art was little more than inferior copying. Hellenistic art was decadence and decline, and Archaic art was valuable only insofar as the seeds of the Classical lay within it. As an undergraduate, I largely recall classical art discussed in terms of its re-interpretation in Renaissance and Neo-Classical art and architecture. Classicism also made an appearance as the antithesis of Modernism, an idea that permeated the studios where the practical curriculum was taught. This was intriguing, given the number of prominent Modernists – such as Pablo Picasso – who had actively engaged with antiquity.

SM: So at university, students of art were being taught that Classicism was anathema?

CvS: Yes, and it struck me that we were being told to actively avoid something that – apart from its outsize reputation – we knew next to nothing about. This ignorance was a necessary precaution since Classicism was deemed so toxic that even thinking about it could corrupt our minds and condemn us to making facile 19th century Academic art forever. I concluded that in that environment any inquiry into Classicism would be doctrinal heresy. Here was an unachievable standard, phantom menace, forbidden fruit, and opportunity for open rebellion all rolled into one.

SM: What then are the main interests that led you in the classical direction?

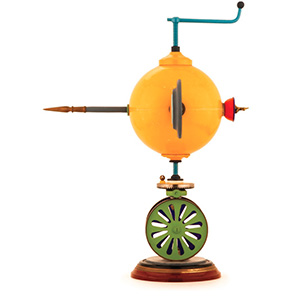

CvS: I have two areas of interest: The dynamism underlying traditions (how they can appear to remain stable while constantly changing). And creative processes. For my Masters in Fine Art I attempted an iconographic revision of the concept of the Classical muse. The idea of the muse had been adapted so many times that it was still current in popular culture. So, it fell within both of my areas of interest. But the image of a female figure holding an identifying attribute was by now so banal that it seemed to lack any ability to communicate the complexity of the idea or what it may have been to begin with. My aim was to do away with the figure and develop a metaphoric object that could do the iconographic work instead. Sculpturally, the project was successful, but in research terms, I felt I had only scraped the surface of the subject.

SM: You then moved into a more specific area, not just the muse but the world of Homer.

CvS: Yes. I had come across Gregory Nagy’s “Greek Mythology and Poetics” (1992). This was my first real encounter with Homeric Studies and I was impressed by how innovative it was. Milman Parry’s emphasis on how understanding or interpreting an artwork requires understanding of how it was made held an obvious appeal to an art practitioner. This kind of theoretical regard for practice I felt was absent from the Art Theory and Discourse courses I took as an undergrad. A few years later I enrolled for an MPhil in Ancient Studies at Stellenbosch University. A main takeaway was the significance of historiography – that the reception of an ancient event, idea or artform represents a type of encrustation or patina that becomes part of the subject that must be negotiated.

SM: How does that come across in your art?

CvS: The objects I use in my assemblages are comprised not only of their form and materiality, but also of layers of accumulated dirt, signs of wear, and sets of pre-existing uses and associations. How these attributes are amplified, altered, or edited is a core feature of a sculptural assemblage. Over the next few years, I tried to get a more comprehensive idea of the debate around archaic Greek poetry and concluded that Homeric theory had created a completely different and very intriguing idea of Homer. To me it seemed a shame that this Homer was largely the preserve of a relatively small group of specialists. Ideas are like gods: they need symbols. If I could visually redefine what is meant by ‘Homer’ and construct an iconography for the notion of Homer, not as a specific person, but something far more abstract – an oral-formulaic poetic system – this idea could begin to acquire a means to travel. A Catalogue of Shapes (2010-13) was the first result of this attempt and Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25 (2018-20) developed these ideas.

See the next post for a more detailed discussion of A Catalogue of Shapes and Powell’s Patterns 2, 11, 20, 25.