This post is written by Michael Brumbaugh, Associate Professor of Classical Studies and an Affiliate in Latin American Studies at Tulane University. His first book, The New Politics of Olympos, was published by Oxford UP in 2019 and his bilingual edition of De Administratione Guaranica (DAG) will go to press later this year. He is currently co-editing a volume on the genre of Greek hymns and completing a monograph on Classical reception in the DAG.

This post is written by Michael Brumbaugh, Associate Professor of Classical Studies and an Affiliate in Latin American Studies at Tulane University. His first book, The New Politics of Olympos, was published by Oxford UP in 2019 and his bilingual edition of De Administratione Guaranica (DAG) will go to press later this year. He is currently co-editing a volume on the genre of Greek hymns and completing a monograph on Classical reception in the DAG.

What’s in Your Classical Library? Finalising a Bilingual Edition of On the Guaraní Way of Life

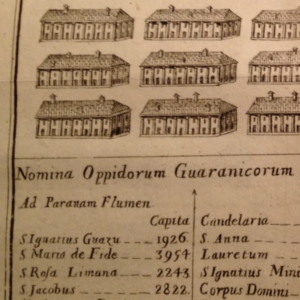

What do Plato, Paraguay, and the French Revolution have in common? This seemingly unexpected confluence of topics is very much on my mind today as I finish up a bilingual edition of José Manuel Peramás’s De Administratio Guaranica Comparate ad Rem Publicam Platonis Commentarius (Faenza, 1793), which translates to “A Commentary on the Guaraní Way of Life in Comparison with Plato’s Republic.” The edition is for a new series from Dumbarton Oaks that seeks to make important pre-modern texts by and about indigenous peoples of the Americas accessible to specialist and non-specialist audiences alike – particularly in the Anglophone world. As such, it will join the growing family of HUP “classic” libraries: the Loeb Classical Library, I Tatti Renaissance Library, the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, and the Murty Classical Library of India.

My hope with this bilingual edition is that the Dumbarton Oaks series will bring this important text to a much wider readership of scholars from a variety of disciplines as well as put the Latin text in the hands of Classicists the world over for the first time since the original 18th century publication. The first translation of the De Administratio Guaranica (DAG) appeared seventy-six years ago, when Juan Cortés del Pino published a Spanish version with an introduction by the prolific Jesuit historian Guillermo Furlong (Buenos Aires, 1946). This landmark translation secured a prominent place for the treatise in Hispanophone scholarship on indigenous history and ethnography as well as the history of the Jesuit Order. Most recently, Francisco Fernández Pertiñez and Bartomeu Meliá published an excellent, revised edition of the 1946 Spanish translation with a press in Paraguay (Asunción, 2004); unfortunately, this edition is also very difficult to obtain. Despite the difficulty of consulting the original text or accessing these translations, the DAG and other works by Peramás have continued to attract scholarly attention, especially throughout the Hispanophone world.

Though written by a Catalan Jesuit missionary, the DAG offers rare, first-hand insights into the indigenous communities of Paraguay in which the author lived for a time, along with broader reflections on human societies and the civic structures that variously oppress and stimulate them. The treatise counters salacious claims of indigenous barbarism levelled by European scandalmongers who had never set foot in the Americas and defends its author and his brethren against accusations of greed and exploitation. As such, it fits squarely within the genre of apologetics that proliferated in response to anti-Jesuit propaganda that succeeded in eliminating the Society of Jesus, which was officially suppressed by Pope Clement XIV in 1773. Yet, in the DAG Peramás takes aim at an even loftier target as he embarks on an ambitious and timely project of political philosophy in which he will teach the European philosophes (public intellectuals) about Plato, and the Guaraní will teach the French Revolutionaries how to run a state.

Nearly ten times longer than Tacitus’s Germania, to which it often refers, the DAG offers a thorough discussion across more than thirty categories (e.g., property rights, education, music) about how Guaraní communities operated in comparison with the institutions and practices Plato identified in the Republic and the Laws as being conducive to fostering a just society. Beyond Plato, Peramás’s work engages closely with dozens of other authors from Greek and Roman literature, the Hebrew and Christian bibles, as well as the works of more contemporary luminaries from the Renaissance and Enlightenment. The treatise is a scholarly tour de force and designedly so, since this bibliographic mastery (of the ancient sources, especially) is fundamental to the construction of Peramás’s own authority. Once again, this is not entirely surprising as such displays of learning were the price of admission for Early Modern authors looking for entrée to the Republic of Letters. What is fascinating about Peramás, however, is how he subverts many of his reader’s expectations. This too seems intentional, since the author, a former professor of rhetoric, has set himself the task of critiquing his audience of European elites without alienating them, celebrating the Guaraní without losing objectivity, and defending the Jesuits without appearing too self-serving.

Sidelined by exile, on his deathbed, and with his text going to press shortly after the execution of French King Louis XVI, Peramás was not in a position to have the impact he might have liked. The revolution plunged France into chaos, the Guaraní Republic was exploited by Spain and ultimately fell into ruin, and Europeans continued to appropriate ancient legacies without understanding them. Even so, the DAG serves as an important witness to ways in which Classical antiquity could be enlisted to magnify the culture and humanity of indigenous peoples such as the Guaraní, offer a critique of colonialism, and contradict European narratives of cultural superiority. Despite failing to change the course of history, Peramás succeeds in offering a compelling picture of the Guaraní as autonomous and independent actors who managed to preserve crucial aspects of their own cultural identity in the face of powerful opposition.