When we wrote this book in 2020-2021, we never imagined the possibility of a second Trump presidential term–yet we face that reality now. With this reality comes an administration and potential cabinet appointments that devalue women’s lives and bodily autonomy in the pursuit of power, control, and capital. In these enduring times of crisis, public feminism will be an even more critical practice of resistance despite the shifting landscape of the social media town square. Given the scope of algorithmic tampering by social media’s investors and leaders, it is more crucial than ever to hold public space for protest beyond such compromised channels. We see the stories that Public Feminism lifts up as such historical and contemporary acts of protest—including Laurel Raymond’s, the anonymous spray-can artist’s, and Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony chronicled below—that may guide our future acts.

In solidarity,

Leila Easa & Jennifer Stager

21 November 2024

Public Feminism in Times of Crisis: From Sappho’s Fragments to Viral Hashtags

Introduction

On the morning of October 22, 2018—about halfway, as it turned out, through the [first] Trump presidency—law student Laurel Raymond encountered something that had not been there the evening before. Someone had used large stencils to paint a quotation in white capital letters across the flagstone entrance to Sterling Hall at Yale Law School. Raymond snapped a picture of the scene and posted it to Twitter.[1] The white paint read: “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter . . .”[2] Flecks of spray can paint had settled around the edges of the stenciled letters to frame the quotation that appeared before the heavy wooden door of the building like a welcome mat.[3] Christine Blasey Ford had spoken these words the previous month during the confirmation hearings for Brett Kavanaugh, a man who—along with a friend—had sexually assaulted Ford at a party when the three of them were teenagers and whom Trump had appointed to the Supreme Court to fill the vacancy left by Anthony Kennedy. To give her wrenching testimony of the assault and its impact on her life, Ford had to relive this trauma on live television, under hostile questioning from senators, and in the court of public opinion.[4] Despite Ford’s sacrifice, Kavanaugh was confirmed to the bench to serve a lifetime appointment. In contrast, Ford and her family were forced into hiding.

When Ford described the way that Kavanaugh and his friend’s laughter had inscribed itself in her brain the night that they assaulted her, she also offered her listeners words for the ways in which trauma endures. In painting Ford’s words onto the steps of Yale Law School—from which Kavanaugh had graduated and from where many students sought prestigious clerkships with the Supreme Court—the painter overwrote the unchecked prestige and power the school (and institutions like it) afforded its graduates through high- level placements in government and the private sector with evidence of the collateral damage such power all too often demands. Although her bravery cost her greatly and did not derail the machine of white male privilege, speaking these words in and to the public etched what had been indelible in her own hippocampus into the public sphere. While the painter’s choice to close the quotation with ellipses might have intended to signal that Ford’s testimony continued beyond the words quoted, it also marks the truth that the work to which she contributed remains unfinished. The ellipses hold space for words, acts, and histories to follow. Within the framework of this book, each engagement with these words—Ford’s testimony, the anonymous spray can artist’s nighttime intervention, and Laurel Raymond’s photograph and subsequent social media post—are acts of public feminism.

Public Feminism in Times of Crisis examines the public practice of feminism in the age of social media and analyzes the deep histories threaded through this new(er) enactment. Although many feminist acts take place in private, public feminism refers to feminist interventions carried out in some form of public sphere. As the internet has moved conversations that were previously shared in closed spaces or as private interactions between individuals into the public, the pre-internet contours of what counts as “public” have changed. We now understand contemporary public space to constitute both virtual and physical spaces.

In this book, we explore the dynamics of this feminism committed in public through the lens of history, and we use history as a framework from which to understand its current and potential future dynamics. We do this to illuminate the ways in which contemporary public feminism acquires its shape and associations. History also, in some manner, teaches us how to perform public feminism. Additionally, our contemporary moment’s access to the tools of global communication—provided in part by social media— radically expands historic possibilities, giving a platform to a wide range of voices while increasing access to information about the historic past beyond the traditional boundaries of academic institutions. This, in turn, changes what we see and value from the past in the present, as well as the ways in which virtual spaces now also circulate and mobilize historical examples in the service of contemporary arguments, whether to advance feminism or to undercut it.

NOTES

[1] Laurel Raymond (@RayOfLaurel), “Entrance to the Yale Law School this Morning,” Twitter, October 22, 2018, 6:14 a.m., https://twitter.com/RayOfLaurel/ status/1054360220971995137.

[2] Jasmine Webber, “A Tribute to Christine Blasey Ford Appears at the Entrance to Yale Law School,” Hyperallergic, October 22, 2018, https://hyperallergic .com/466934/a-tribute-to-christine-blasey-ford-appears-at-the-entrance-of-yale-law -school.

[3] The spray can intervention paralleled Black Lives Matter protesters who spray- painted on top of confederate statues and empty plinths—and who left cans of spray paint for others to use. Our photo for this chapter (Fig 0.1) captures a related practice of projection onto these statues.

[4] Bonnie Honig, Shell Shocked: Feminist Criticism After Trump (New York: Fordham University Press, 2021), 92–7.

Abstract:

Public Feminism in Times of Crisis examines the public practice of feminism in the age of social media. While their concept of public feminism emerges from a moment of acute crisis (the Trump years and the Covid-19 pandemic), Leila Easa and Jennifer Stager locate its foundations in history, journeying through broad swatches of time looking for connections between the centuries through art and literature and culture. Each chapter focuses on what public feminists do in the world: Public feminists gain control over an archive that otherwise contains or excludes them; they recover their own stories and subjective experiences, sometimes for activist use; they examine images and language that construct women in patriarchal texts; they situate the individual within a collective and the collective within an individual; they confront the limitations of such situating due to the containment of patriarchy and reclaim new systems of power in response; and they resurface a deep history for the alternative strategies of memorializing they employ. In navigating these practices, the authors also attend to the material conditions of writing histories as well as those shaping and enabling public feminist acts and protests more broadly.

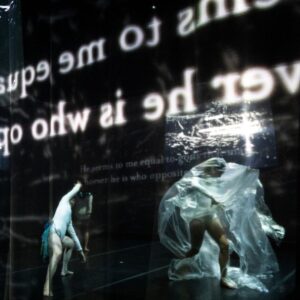

Caption for image:

extreme lyric I, a dance theater collaboration between Maxe Crandall and Hope Mohr, featuring Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho and projection design by Ian Winters. Dancers pictured: (L to R) Tara McArthur, Suzette Sagisi, Jane Selna. Not pictured: Karla Quintero. Photo by: Robbie Sweeny