This post is written by Federico Brusadelli, Assistant Professor of Chinese History, University of Naples “L’Orientale”.

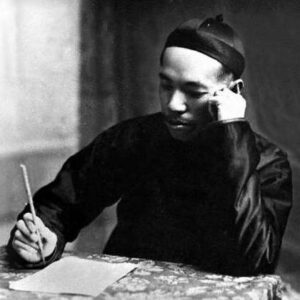

In 1902, Liang Qichao 梁启超 (1873-1929) – a writer, philosopher and historian on his way to becoming the most influential Chinese public intellectual of his generation – published in his own journal The New Citizen two essays dedicated to the ancient Greek poleis (city-states), Athens and Sparta. At a time when the imperial system was crumbling, and a greater knowledge of the “external world” (i.e. beyond China) seemed crucial for the salvation of the country, interest turned towards the origins of “Western” political culture.

Liang’s two essays provide an important example of the Chinese reception of the ancient Greek polis, which was the (imagined) cradle of many things considered “Western”, from urban culture to democracy. They might form an essential part of a broader investigation of the perception, diffusion and narration of the “Western Classical” in the “Chinese Modern”, and of its function in the rearticulation of the Chinese conceptual and political landscape.

But there’s more to this. In the specific case of the polis as-a-concept. As it has been recently pointed out by Hans Beck and Peter Funke, “the world of ancient Greece witnessed some of the most elaborate experiments with federalism in the pre-modern era” (Beck & Funke 2015). “Federalism” experienced a short but intense success in early-20th-century China, since the Revolution of 1911 originated from provincial secessions and was sustained by a rhetoric of local empowerment. The reflections, therefore, on the prototypical “self-governing urban space” of the ancient Greek polis produced by intellectuals of the Chinese Sattelzeit (Vogelsang 2012) can support a study of the Chinese conceptualisation of the increasingly important urban space, and illuminate how key concepts such as “self-government”, “autonomy”, or “shared sovereignty” were approached, transferred and used for the articulation of competing political agendas, before the failure of federalist experiments in the late 1920s (Dirlik 1996; Brusadelli 2023).

Let’s return to Liang’s essays on the polis, then, and consider them as a crucial passage in this story of receptions and reflections. Prior to Liang, interest in the Greek polis was embedded in the first, often confused, waves of interest in all things Western. In the works of mid-19th-century Chinese intellectuals, Europe was either “otherised” (occidentalised, we could say) as an exotic and barbarian land of scientific wonders and socio-political curiosities, or it was explored through the philosophical and historiographical framework of Classicisim.

Kang Youwei 康有为(1858-1927), Liang’s teacher, was among the proponents of a radical restructuring of the Empire largely influenced by knowledge of the West, but still based on the traditional Chinese philosophical and conceptual repository. Kang’s use of such a classical perspective on Western modernity is confirmed by the following passage from a political essay written in 1917, but still fully representative of his earlier commitment to the ultimate blending of East and West in a new form of Confucian universalism (Brusadelli 2020).

Confucius thus comments on the qian hexagram from the Book of Changes: “To see dragons with no head. Auspicious.” The Commentary of the Images says: “Qian originally uses nine and rules the world.” Where do its political implications lead us to? In Greece, where there was an assembly of people chosen for their merits; in Rome, where there were a Senate and a triumvirate, with senators all chosen for their political prominence or for their personal reputation. In Germany, where seven Prince-electors used to nominate the king; in Switzerland, where there are seven ministers who in turn act as president for a year-long mandate; in the United States of America, where each State chooses two delegates for the Senate, which is charged with supervising the President and controlling him on foreign policy and great issues; and at the time of the Zhou, when the Republic of Zhou-Shao was established (Kang 1982: 1047-48).

The reference to the Greek polis is introduced by a hexagram from the Yijing, and is correlated to other political structures – both Chinese and foreign – that have one aspect in common, namely the absence of an individual leadership. The “proto-federal” nature of ancient Greece is thus lumped together by Kang with models as diverse as Switzerland or the Zhou dynasty, portending a view of history and morality that is still rooted in Confucian universalism.

Liang is certainly inspired by and indebted to Kang’s “opening” of the Chinese intellectual horizons, but at the same time he expresses a very different “scientific” interest in what we could call the “non-Chinese political”. This aspect is a vital part of Liang Qichao’s cultural and political endeavour. As a translator he integrated this philosophical engagement with a set of conceptual innovations, transplanting into the Chinese discourse some of the pivotal components in the political vocabulary of modernity into Chinese (from “nation” to “democracy”). As an essayist, Liang was in those years analyzing and comparing the institutional systems of the world, in a precious informative effort that would help the Chinese public become familiar with Euro-American political culture. As a political philosopher, in continuity with his journalistic activities, he provided a seminal contribution to the development of Chinese theory of “citizenship”, “free will”, and “liberty” (Lee 2007). The analysis of ancient Greece was necessary to familiarise the Chinese audience with a less threatening version of Euro-american political culture – one that was chronologically coincident with the golden age of Chinese classicism, and distant from the age of humiliations.

By this token, Liang’s two essays on Athens and Sparta clearly historicise and contextualise the polis experience, refusing any exoticisation of the so-called West, and try to distinguish cultural peculiarities from possible universalities. As for the contents (not particularly exciting in terms of novelty, being a rather linear summary of the city’s political and cultural history), Athens is unsurprisingly praised by Liang as the “cradle of democracy”, and is associated to concepts like “freedom (ziyou 自由)”, “progress (gaijin 改进)”, “culture (wen 文)”, “equality (pingdeng 平等)” (Liang 1999: 875). And yet the contrast to Sparta is not presented as a good-vs-evil pattern, but as a sort of yin-yang complementarity. Spartan authoritarianism, Liang argues, is quite different from the Chinese one, as it was ultimately based on the “authority of the people” (minquan 民权), rather than on the power of the ruler. In this sense, the political system of Sparta is presented as a form of “proto-constitutionalism”. Power and sovereignty, Liang explains, were shared (two kings, five ministers, the assembly), and even if they were unequally distributed among classes, Spartans are defined citizens (guomin 国民), and not subjects (chen 臣) as the Chinese under the imperial autocracy (Liang 1999: 865-866). The survey of Sparta offers Liang an opportunity to stress how education (that in the ancient Spartan polis included women) works as the foundation of patriotism, and to bemoan how smaller countries (even as small as a city-state) can be much stronger than huge polities (as the vast and humiliated Qing Empire…).

It’s Sparta, then, that might represent an example more valuable for early-20th-century China than the apparently almost utopian Athenian experiment with democracy and equality:

The militarist spirit should be the primary foundation for a nation. This is now shared knowledge, and from now on the twentieth-century world will be permeated with this idea. Those nations who do not adopt militarism will certainly not stand firmly between heaven and earth. So, it is clear that for the responsible citizen of the future, it will not be sufficient to learn from Athens alone for self-perfection. […] Sparta is truly the best remedy for today’s China (Liang 1999: 866).

Trying to hold together both the Athenian horizon and the Spartan spirit in his blueprint for China, Liang’s almost utopian aspiration was to blend individual freedom and collective strength into a coherent project of State-building and national salvation – an oscillation between “democracy” and “authoritarianism” that will continue to haunt many of his fellow Chinese intellectuals and political activists for the rest of the century.

In the following decade, Liang’s introduction of a serious analysis of Euro-american political thought will prove seminal for the first generation of Chinese professional political scientists. Such is the case of Zhang Weici 张慰慈 (1890-1976), an interesting and as yet understudied protagonist of the Republican milieu.

After earning a PhD in the USA, at the University of Iowa, Zhang returned home to become the first professor of Political Science at Beijing University. As the author of the first Chinese comprehensive studies of British and American political systems, Zhang’s activities contributed to the highest peak of Chinese liberalism in the 1920s and were characterised by a strong interest in municipal governance (a result of his American education) and a preference for federal systems and theories of “shared sovereignties”. Close to the Guomindang, and to their evolutionary view of constitutions (supporting the necessity of a period of tutelage over a still immature China), Zhang would eventually leave academia to embark on a bureaucratic career in Nationalist China in the 1930s. Remaining in Shanghai after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Zhang’s aforementioned interest in urban governance led him to an in-depth study of the history of Western municipalism.

In his essay “The system of municipal government (Shizheng zhidu 市政制度),” written in 1925, Zhang adopts a linear, Hegelian, trajectory to identify three historical phases in the urban history of Europe: city as states (antiquity), gradual merging of city in States (medieval-modern), cities as advanced spaces within nations (contemporary). Within this narrative, Greek culture is defined by Zhang “entirely a culture of the city”, the expression of an “urban society from the beginning”. And yet, Zhang stresses how that urban culture was polymorphous: institutional systems vary from polis to polis, and even across the history of the same polis. Accordingly, he de-mythizes the association between polis and democracy, reducing deliberative democracy to one stage in Athenian history and highlighting the peculiar geographic factors that provided Athens the opportunity to privilege democracy over authoritarianism – namely the “natural protection” of mountains and sea from external enemies. Historical contingencies notwithstanding, Zhang still wishes to highlight two conceptual features that consistently underlie the polis experience, and that in his opinion might prove a valuable example for China: first, the foundational role of citizens “participation” in the administration, and secondly the conceptualization of individual and communal “interests” as inseparable and not in conflict (Zhang 2019).

Again, the struggle to maintain the democratic horizon in the visual range of a country that was plagued by instability and pervaded by radical impulses.

If Kang, Liang and Zhang are united by their effort in using Western models (polis included) to shape a path for China’s nation-building efforts, another intellectual in the same years would look at ancient Greece with different aspirations. Zhou Zuoren 周作人– the only trained Greek scholar and translator, and brother of the more famous writer Lu Xun 鲁迅 – would use his knowledge of classical aesthetics for the elaboration a “humanistic modernity” in opposition to the “nationalist” esprit dominating those decades. Albeit Zhou never penned any work of political science or history, his intellectual immersion in the polis lived in his participation to the movement of the “New Villages”, utopian experiments of small-scale local self-governance launched in Japan and praised by Zhou already in 1919 (Zhou 2009). As pointed out by Susan Daruvala, “we find in Zhou a construction of China that depends on the diversity of individuals and localities and is not threatened by outside influences but welcomes them. These are major differences with the dominant construction of the nation in Chinese literature for most of the twentieth century” (Daruvala, 2000: 242)

As demonstrated by this brief study of the Chinese reception of the ancient Greek polis, different authors refracted their own different concerns through the ancient Greek experience: the creation of strong communities, the valorisation of the modern urban dimension, militarisation, democratisation, even forms of anarchism which resemble Daoism. A “modern” kaleidoscope, soon to be silenced by the strongly centralist and Statist agenda embraced by both the Nationalist and the Communists at the end of the 1920s.

Bibliography

Beck, Hanse, and Peter Funke (eds.), Federalism in Greek Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Brusadelli, Federico, Confucian Concord: Reform, Utopia and Global Teleology in Kang Youwei’s Datong Shu, Brill, 2020.

—————————-, “From Modern to Feudal: Conceptual Articulations of Federalism in Republican China”. Contributions to the History of Concepts 18, 2, 2023, pp. 64-79.

Daruvala, Susan, Zhou Zuoren and an Alternative Chinese Response to Modernity, Harvard University Press, 2000.

Dirlik, Arif, “Social Formations in Representations of the Past: The Case of ‘Feudalism’ in Twentieth-Century Chinese Historiography”. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 19, 3, 1996, pp. 227-267.

Fan, Xin, World History and National Identity in China. The Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Hon, Tze-ki, The Allure of the Nation: The Cultural and Historical Debates in Late Qing and Republican China, Brill, 2015.

Kang Youwei, Kang Youwei Zhenglunji [Political Writings] (edited by Tang Zhijun), Zhonghua Shuju, 1982, 2 vols.

Lee, Theresa Man Ling, “Liang Qichao and the meaning of citizenship: then and now”. History of Political Thought, 28, 7, 2007: pp. 305-327.

Li Tonglu, “To Believe or Not to Believe: Zhou Zuoren’s Alternative Approaches to the Chinese Enlightenment”. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 25, 1, 2013, pp. 206-260.

Liang Qichao, Liang Qichao quanji [Complete Works], edited by Yang Gang and Wang Xiangyi, Beijing chubanshe, 1999.

Liu, Lydia H., Translingual Practice: Literature, National Culture and Translated Modernity, 1900-1937, Stanford University Press, 1996.

Renger, Almut-Barbara, and Xin Fan (eds.), Reception of Greek and Roman Antiquity in East Asia, Brill, 2018.

Schulz-Forberg, Hagen (ed), A global conceptual history of Asia, 1895-1940, Pickering & Chatto, 2014.

Vogelsang, Kai, “Conceptual History: A Short Introduction”. Oriens Extremus 51, 2012, pp.9-24.

Zhou Yiqun, “Greek Antiquity, Chinese Modernity, and the Changing World Order”, in Ban Wang (ed), Chinese Visions of World Order. Tianxia, Culture, and World Politics, Duke University Press, 2017, pp. 106-128.

Zhang Weici, Shizheng zhidu [The System of Urban Government] (1925), Beijing chubanshe, 2019.

Zhou Zuoren, Zhou Zuoren sanwen quanji [Complete works], Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe, 2009.