How can ancient tragedy be transplanted into the modern medium of film? What are some of the obstacles filmmakers have to overcome when they attempt to transform an ancient theatrical play into a movie? What challenges do we face when we use their films in our classrooms? And finally, is there ever a point beyond which we should stop referring to a film as a ‘reception’ of an ancient drama(s), or could we even talk about the reception of the very concept of ancient tragedy itself? These are some of the exciting questions that scholars working in this area have been engaging with and the discussion is ongoing, so join in!

Mine is a very specific way of addressing these questions. Among the rich and varied history of the cinematic reception of ancient Greece, the films of modern Greek directors deserve special attention, because of the particular form this dialogue between classical antiquity and modernity has assumed. Modern Greece lays claim to a ‘special relationship’ with what it views as its classical past. This national obsession has had a corresponding impact on its culture and the arts. As a Greek, this phenomenon has long fascinated me, so the decision to investigate more closely the work of filmmakers who transplanted Greek tragedy and its stories, themes and characters into the modern medium of cinema, seemed like a natural fit. After all, Reception Studies encourage us to examine closely our own preconceptions, and how they affect not only what we study, but also from what perspectives we approach our material. So, I should add to this list my deep and abiding love of film and a firmly held belief in the value of investigating popular culture. After all, Greek drama was the popular entertainment of its day.

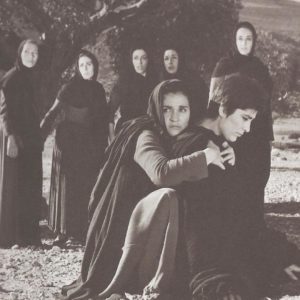

Modern Greek cinematic receptions can help us explore the artificially constructed divide between high art and popular culture. Nowadays, Greek drama is considered high art, but the medium of film is undeniably a popular one (despite the best efforts of art-house cinema which has a narrower audience). So, how do you transplant an ancient play laden with cultural capital into this modern popular medium? Modern Greek directors have adopted a variety of approaches to this thorny problem, but have tended to place themselves at the extreme ends of the spectrum between close adaptations and creative new works. George Tzavellas (1916-76) took up this challenge first with his Antigone (1961), but it is generally held that it was the Greek-Cypriot Michael Cacoyannis (1922-2011) who made the first successful attempt with his Electra (1962). The problem was that Tzavellas stuck too closely to the theatrical roots of his source material, by having his actors declaim their speeches in an overly formalized manner typical of modern Greek productions of ancient drama of that time. In contrast, Cacoyannis respected the requirements of the new medium and sought to ensure that Greek tragedy enjoyed a wider audience by adopting a number of Hollywood techniques that made the ancient material more accessible; a case of know thy audience?

Modern Greek cinematic receptions can help us explore the artificially constructed divide between high art and popular culture. Nowadays, Greek drama is considered high art, but the medium of film is undeniably a popular one (despite the best efforts of art-house cinema which has a narrower audience). So, how do you transplant an ancient play laden with cultural capital into this modern popular medium? Modern Greek directors have adopted a variety of approaches to this thorny problem, but have tended to place themselves at the extreme ends of the spectrum between close adaptations and creative new works. George Tzavellas (1916-76) took up this challenge first with his Antigone (1961), but it is generally held that it was the Greek-Cypriot Michael Cacoyannis (1922-2011) who made the first successful attempt with his Electra (1962). The problem was that Tzavellas stuck too closely to the theatrical roots of his source material, by having his actors declaim their speeches in an overly formalized manner typical of modern Greek productions of ancient drama of that time. In contrast, Cacoyannis respected the requirements of the new medium and sought to ensure that Greek tragedy enjoyed a wider audience by adopting a number of Hollywood techniques that made the ancient material more accessible; a case of know thy audience?

Cacoyannis went on to make two more films based on Euripides’ dramas The Trojan Women (1971) and Iphigenia (1977). The director’s creation of a trilogy of films that is closely modeled on three ancient Greek plays remains, to this day, a unique achievement. More important, at least from a pedagogical perspective, is the fact that his Euripidean trilogy is ideally suited for the classroom. Students respond strongly to his movies precisely because they are accessible and offer a relatable interpretation of their source texts. A close comparison between source and reception reveals why Cacoyannis’ focus on the family, the question of good leadership and his strong anti-war bias is so attractive today. His movies can help students reflect on both source text and reception.

At the other extreme of the spectrum, that of ‘new work’, stands Theo Angelopoulos (1935-2012), whose films often deliberately mask their connections to ancient Greece. There are, however, strong hints that a knowledgeable audience familiar with ancient Greek literature can easily pick up. At the most obvious level, ancient names and characters populate his movies – Alexander the Great, Helen, Odysseus, Orestes, and more – but the context is always modern Greece. These are not simply modern versions of their ancient counterparts. Crucially, however, they retain some of the key aspects of their classical sources often on the level of narrative. Angelopoulos subtly reinforces these connections on the visual plane. The controversial director sought to problematize Greece’s obsession with the classical past and to illustrate the dangers of said past becoming a burden, rather than an advantage. Angelopoulos did not set out to film a Greek tragedy, like Tzavellas and Cacoyannis, but in my view he deliberately forged connections with the ancient genre and the concept of tragedy itself, as he understood it. Indirect receptions like the ones on offer in his cinematic oeuvre leave a lot of room for discussion and encourage us to re-examine the very processes of reception and our understanding of it.

Ultimately, the fundamental problem that confronts modern Greek filmmakers is the same as that which faces the country’s theatre practitioners. Productions of ancient plays in the modern state are saddled with the need to somehow ‘prove’ our country’s claim of a special relationship with ancient Greece. As a result ‘fidelity’ to the ancient source texts is generally perceived as the best way to stage or film Greek drama. This has helped to create a rigid set of hierarchies in which fidelity has become intrinsically linked to ‘Greekness’. But, in the popular medium of film, Tzavellas’ lavish adaptation of Sophocles’ famous play failed to connect with its viewing public. Angelopoulos’ art-house films, on the other hand, offer highly creative adaptations that demand a knowledgeable audience for the connections to be made, and is addressed to an ‘elite’ audience interested in cinema as high-art. Modern Greek cinematic adaptations thus help to expose the deep fault-lines in the reception of Greek drama in the modern state and raise interesting questions about the range of possible responses to ancient Greece on screen.

An Athenian, born and bred, Anastasia Bakogianni completed her higher education studies in the UK where she caught the classical reception bug early on from Maria Wyke. After completing her PhD at the University of London, she worked at various UK institutions, including The Open University (2009-13). In 2016 she moved to Massey University in New Zealand where she continues to pursue her interests in classical reception studies, in particular cinematic adaptations of ancient tragedy.