After languishing in film and television obscurity for several decades, biblical stories have made a remarkable comeback in the past decade or so – thanks in no small part to the blockbuster success of The Passion of the Christ (2004). Many other productions have followed in its wake, some larger (Exodus, Noah), some smaller (The Nativity, Sant’Agostino, The Young Messiah), but the general trend is clear: the Bible is back. But in the midst of the ‘War on Terror’, this is an odd phaenomenon: while on the one hand some major films like Agora have cast Early Christianity in the same fundamentalist light as contemporary religious extremists, on the other hand we see a proliferation of overtly religious films and TV series geared towards a religious (predominantly American Protestant) audience. In an era of increasing scepticism or perhaps wariness towards religion in general, it’s fascinating to see over(t)ly preachy big-budget productions like The Bible appear on The History Channel, of all places, only to be followed up by the brilliantly-named A.D.: The Bible Continues on NBC.

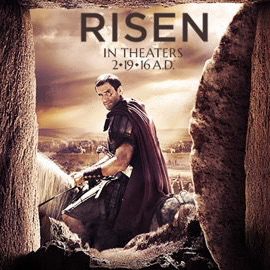

With something of a saturated market, then, it’s perhaps easy to see how one film that straddles this divide would have slipped under the radar: Risen, directed by Kevin Reynolds and starring the brooding Joseph Fiennes as Clavius, a Roman tribune serving under Pontius Pilate at the time of the Crucifixion. The film is a bit of a paradox: while it engages with the same material of the Passion and its aftermath that we have seen in many of the ‘religious’ productions I’ve described above, it does so in a vastly different way. The familiar story is approached from an oblique angle: Clavius is off putting down a small revolt and returns to Pilate in Jerusalem just as Christ dies on the Cross.

The rest of the 107-minute film weaves something of an old yarn: the dutiful Roman soldier is tasked with guarding the tomb of Christ to prevent further unrest, and then after the Resurrection he delves into the hidden Christian community of Jerusalem looking for the disappeared body. As he does so, he confronts his own weariness and ambivalence at his service to Rome, and through meeting several prominent apostles he is brought to closer to meeting Christ. When he does, he has a moment of conversion, and abandons his service to Rome in order to help the apostles escape to Galilee. He follows, helping them avoid the pursuing Romans, and then his time with first the apostles and then Christ himself at the Sea of Galilee inspire him to set out and share what he has found.

The story of a Roman conversion, of course, is an old one that we have seen everywhere from St. Longinus and Cornelius to The Robe (1953) and The Sign of the Cross (1932), but what sets Risen apart is how explicitly it grafts the politics, vocabulary, and even tactics of the contemporary War on Terror onto the immediate aftermath of the Crucifixion. Jerusalem becomes something akin to occupied Iraq or Afghanistan: a foreign, technologically-superior force tries desperately to maintain some measure of order and peace among warring religious factions, only to find itself dragged inevitably into the fray. The Romans of the film try to pacify the province by allying themselves with the Sanhedrin, but the Christians and other extremist factions despise both the occupiers and their collaborators.

We see this state of affairs emerge as early as the first main scene of the film: as the Romans attack an encamped rebel group, Joseph Fiennes’ voiceover laments that ‘each day creates more zealots to challenge the rule of Rome and bring freedom. Instead, we bring them death.’ Interestingly, the rebel group Clavius seeks to put down is led by none other than Barabbas, whose freedom the crowd demanded from Pilate instead of Christ. Barabbas remains a fanatic until the very last, as he shouts at Clavius, ‘it must pain you to know that the one true god chooses us over you… when the Messiah comes, Rome will be nothing!’

We see this state of affairs emerge as early as the first main scene of the film: as the Romans attack an encamped rebel group, Joseph Fiennes’ voiceover laments that ‘each day creates more zealots to challenge the rule of Rome and bring freedom. Instead, we bring them death.’ Interestingly, the rebel group Clavius seeks to put down is led by none other than Barabbas, whose freedom the crowd demanded from Pilate instead of Christ. Barabbas remains a fanatic until the very last, as he shouts at Clavius, ‘it must pain you to know that the one true god chooses us over you… when the Messiah comes, Rome will be nothing!’

The Romans, for their part, are uninterested in such doctrinal disagreements, and Pilate is only driven to keep the peace in order to save his own career with a visit from the Emperor Tiberius approaching in a few months’ time. The Romans, as we have seen with some forces of the 21st century, treat religious divides as political divides, much to the detriment of all involved.

Many further echoes of the post-9/11 world can be heard throughout the film. While questioning prisoners (Christians) he has taken by paying informants, Clavius threatens them with more aggressive means of interrogation. The conflict between Rome and these insurgents is far messier and more brutal than conventional warfare: speaking to his young lieutenant fresh from Rome, Clavius narrates a horrifying episode in which Romans were captured, tortured, and impaled, concluding ‘that is why you can offer no quarter’. Steps taken to calm civic unrest are viewed as religious transgressions, especially in a striking scene in which Roman soldiers in armour dig up Hebrew graves as a decidedly middle-eastern crowd looks on in protest.

This war of occupation has similar tactics to the War on Terror, as Roman soldiers slip through the city in disguise while hunting for religious extremists, only to throw off their cloaks and go kicking down doors in search of their target. Ethnic politics are of course at play, as the largely Caucasian, European-looking Romans try to pacify a Jewish and Christian populace that looks distinctly middle eastern – a trope that was noticed by Jim Slotek of the Toronto Sun, who wrote whimsically that ‘It’s nice to finally see the Messiah portrayed by somebody who’d probably get extra attention at a U.S. airport by Homeland Security.’ The Ancient World, yet again, has been cast a decidedly modern conflict.

So what do we see in this film? A conversion story or just someone’s experience of the turbulent political and social climate after the Crucifixion? Is this an illustrative take on an old narrative from a very new angle, or is this simply the retro-jection of a 21st century world with which Antiquity would have been fundamentally unfamiliar? As ever, cultural artefacts such as this provide us ample food for thought and reflection, and here as elsewhere we wonder whether such thoroughly modern depictions of Antiquity teach us more about then, or now.

Dr Alex McAuley is Lecturer in Hellenistic History at Cardiff University. In addition to his work on changing perceptions of Antiquity in the 21st century, he also works extensively on ‘globalisation’ and cultural exchange in the Hellenistic World, as well as dynastic practice and ideology of the Hellenistic Dynasties.