Carla Bocchetti, associate member of the French Institute in South Africa IFAS-Research and author of the African takeover Blog 7 reports on her fascinating exhibition on Homer and the Indian Ocean in Maputo, Mozambique. This project aims to de-centre the Odyssey of Homer and juxtapose this epic tale with narratives, texts and landscapes from the coast of the Indian Ocean.

Homer and the Indian Ocean

By Carla Bocchetti

The Odyssey of Homer is considered to be a foundational text in the European tradition and one of the bases of cultural Western hegemony. The purpose of this exhibition “Homer and the Indian Ocean” is to de-centre the Odyssey from that tradition, and to revise the European idea of the Odyssey as a “universal” text. To do that, I will juxtapose the epic with histories and narratives coming from the shores of the Indian Ocean. My aim is to include new voices and new landscapes, which will expand the geography of the poem beyond the boundaries of the Mediterranean Sea.

Eratosthenes (3rd century BCE), who measured the circumference of the earth, was of the opinion that the wanderings of Odysseus were fiction and could not be located on a real map. He is famous for his statement: “You will find the scene of Odysseus’ wanderings when you find the cobbler who sewed up the bag of winds”. My work is based on Odyssey book 11, Odysseus’ visit to the Underworld (a famous book that indirectly, via Vergil, inspired Dante Alighieri’s Inferno); and I use a visual form to study the way in which geography intersects with text. Many researchers, especially Victor Bérard, place the journeys of Odysseus in Italy: well-known are his locating Circe in the Aeolian islands, Hades in Etruria, and Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis in the Strait of Messina. But to place the Odyssey in new regions of the world, as Derek Walcott did with his “Odyssey” in the Caribbean, opens up the possibility of exploring the Indian Ocean as another originator of narratives and intersecting histories coming from the East African Coast, South Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. “Azania” and “Rapta” – names that denote the East African coast in the Greek geographical work, The Periplous of the Erithrean Sea (1st century CE) – can acquire new meanings when studied from a perspective that emphasizes global encounters.

Background

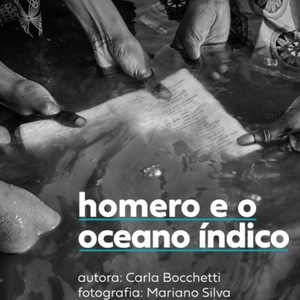

Inspired by the work of the Luxembourg-based Portuguese artist Marco Godinho, Written by Water, exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2019, this exhibition “Homer and the Indian Ocean” creates the fiction of the sea erasing and re-writing the Odyssey with new characters and stories of migration, with a geography that follows circuits of return (nostos) based on the pattern dictated by the monsoon.

To study the material culture of the Indian Ocean, for example, its mercantile trade in Chinese and Portuguese pottery (fragments of which can still be found on the shores of Ilha de Mozambique), opens up the option of approaching the Graeco-Roman world through the lenses of global history.

Global History conceives the world as flat, without a vertical hierarchical organization, and is based on large geographical areas connected by interoceanic trade. That perspective has made it possible to revise the dialectic center-periphery, colonizer and colonized, and other ideas coming from postcolonial studies. At the same time, Global History has made it possible for Classical Studies to establish a dialogue with disciplines to which it is normally not related.

The presence or absence of Homer in the Indian Ocean, can give different layers of meaning to the idea of the Ocean as an author of the Odyssey, writing about slavery, migration, indentured labour and many other problems that Mozambique shares with the African continent, especially when connected with the regional perspective of the Mozambican diaspora in South Africa.

Installation 1

The Odyssey of Homer is submerged in the waters of the Indian Ocean in a symbolic act that features the sea as capable of erasing and re-writing Homer. The Odyssey belongs to an oral tradition of several centuries and consists of material from different periods and regions of Greece fused together into a long epic poem. To submerge the book makes reference to the oral tradition of Africa, to the fact that it can be possible to narrate other stories emphasizing points of cultural convergence instead of difference.

Installation 2

Greek Capulanas. Costa do Sol. Maputo, Mozambique.

This section highlights the importance of African women in global narratives. Writing passages of Homer Odyssey book 11 on Capulanas creates a dialogue between antiquity and Africa; Homer’s Odyssey gives the option of projecting other peoples’ lives, other geographies and new landscapes, a cartography in which European history crosses paths with stories written in other seas.

The liquid world that flows between the visual and written culture creates a new methodology that invites us to reconsider traditional aspects of Classical Studies, such as the idea that the Classics have a civilizing mission outside Europe. It opens up the opportunity of creating a dialogue between cultures and disciplines outside the traditional spheres in which the Classics have previously been studied.

(Odyssey 11.210-214)

Mother, why will you not let me touch you?

Even in Hades, we could hold each other,

Both taking some cold comfort in our tears.

Or it is just a phantom that Persephone

Has sent here to swell my pain and sorrow?

Installation 3

Shield of Sand. (Odyssey 5.278-281)

For seventeen days he voyaged across the water,

then, on the eighteenth, shadowy mountains rose,

where the Phaiakian land was close to him

as it lay like a shield out on the misty sea.

The Bag of the Winds (Odyssey 10.17-26)

When I asked to continue on my way,

to be sent off, he did not refuse, but sent me.

He gave me a bag, made from flayed ox-hide

and bound inside the ways of the blustering winds;

for Zeus had made him keeper of the winds,

able to stop them all at will, or make them blow.

On board, he tied this bag with a shining

silver cord, so not the least breeze could escape,

and sent a westerly wind to blow for me,

to convey my ships and men.

The companions of Odysseus open the Bag of the Winds, and a great tempest drives Odysseus’ ship off, far from his homeland. Global history focusses on movement and interoceanic routes, and enables one to reconsider themes such as slavery, sugar plantations, forced labour, mining and railway construction as narratives written on the pages of the Ocean – writing invisible as the blindness of Homer. The movement of people, ideologies and trade, together with port cities and islands are part of a narrative written in water, stories that get modified when found in different geographical locations and landscapes, performing new Odysseys where actors and spectators inscribe their lives in the library of the sea.

Pages from books of Mozambican writers, previously submerged in the sea, such as Paulina Chizane, Noémia de Sousa, Jose Craveirinha and Mia Couto, and South African writer Koleka Putuma, are in dialogue with Greek words coming from the world of the heroes and heroines of the Odyssey, words such as kleos (fame), agathos (good), kalos (beautiful). These Greek words appear together with words from the South African Nguni languages (especially Zulu and Xhosa) used in the translation by Richard Whitaker, The Odyssey of Homer: A Southern African Translation: inkosi (chief), magogo (grandmother), imbongi (singer). Along with them, there is a selection from Luis de Camões, Canto Six of The Lusíads, pointing to pastoral life that interacts with the sea – the oar of a ship is also a tool to plough the land – and creates a liaison between the worlds of travel, agriculture and the pastoral (machambas), that all participate in writing the history of the sea.